Natalie Murray (Collections and Exhibitions Manager) takes a look at one of the French painters who features in the Light & Soul: Early Impressions of The French Landscape exhibition at The Cooper Gallery

Light & Soul is the culmination of a research project into the French drawings and paintings at the Cooper Gallery, funded by the Headley Fellowship through Art Fund. The project focused on the 19th century landscape artists, including those who worked in the Forest of Fontainebleau and along the coastal areas of Normandy. The research also revealed some of the wonderful examples held in other collections and we are delighted to welcome remarkable paintings on loan from Sheffield Museums, York Museums Trust, Leeds Museums and Galleries, The Bowes Museum and The National Gallery, London, displayed alongside the treasures from the Cooper Gallery collection.

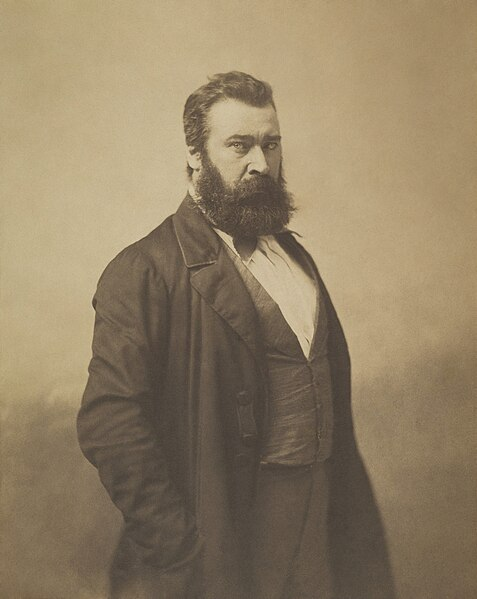

Jean‐François Millet (Metropolitan Museum, New York)

Millet was a pioneering figure in the group of artists at Barbizon but differed in the greater focus he placed on the people in rural landscapes and scenes, making them the centre of his artworks. Of the three painters in this section, Millet was the one whose work most often generated questions about his politics from the late 1840s onwards. This was because the agricultural labourers he chose to portray were often the poorest of the poor, as demonstrated

in the drawings in the exhibition. Millet was born in the small hamlet of Gruchy, on the Normandy coast west of Cherbourg. He lived with his parents, grandmother and seven brothers and sisters in a house which his family had occupied for generations. His parents, Jean Louis Nicolas Millet and Aimée Henriette Adelaïde Henry, were farmers and, as they were greatly occupied with this and a large family, the young Millet spent a lot of time with his grandmother,

Louise Jumelin Millet. She greatly influenced Millet’s outlook on life with her compassionate nature and religious commitment.

The family were of modest means and Millet’s rural childhood was not impoverished. He attended the village school, an education which included both Latin and the classics, and showed an interest and talent for drawing as a child. Having a family supportive of his

artistic skills meant that he could leave working on the farm to study art in Cherbourg, which led to a scholarship in Paris, the École des Beaux-Arts and the studio of the extremely popular history painter Paul Delaroche (1797-1856). Millet’s arrival in Paris in 1837 and the following 12 years presented a variety of opportunities and misfortunes for him. Paris did not agree with the young artist from rural Normandy. He found the great mass of people, the noise

and dirt overwhelming and was so embarrassed to ask his way through the streets, it took him several days to find the Louvre which he so wanted to visit. Once successful in locating it, he sought sanctuary there most days, absorbing and embracing the works of the Old Masters.

After two years with Delaroche and a failed bid to win the Prix de Rome, Millet changed to a drawing academy and had his first painting accepted at the Salon in 1840. Two years painting portraits in Cherbourg followed, then a return to Paris with a new wife, Pauline Virginie Ono, who died soon after in 1844. Returning to live in Cherbourg followed by Le Havre, he met Catherine Lemaire, the woman with whom he spent the rest of his life and had nine children.

Artistically it took Millet a long time to find his chosen subject matter. His first period in Paris was invaluable for the academic training he received, particularly in figure drawing. He made

a living by painting portraits and genre scenes and in the mid-1840s he was creating large-scale history paintings of religious and mythological subjects. His skill in depicting the female nude

figure in particular was something admired and commented on by critics and collectors, but Millet wasn’t satisfied with such subjects and he began to look at the rural scenes in the area around Montmartre, near his studio at the time. The moment of greatest significance for the rest of Millet’s career came in 1849 when he moved to Barbizon with his family to escape political unrest and the cholera outbreak in Paris. It was Charles-Émile Jacque (1813-1894),

an artist with a large family who was a good friend and neighbour, who suggested to Millet that they should move their households to a small village he knew on the edge of the Forest

of Fontainebleau. Millet was to make Barbizon his home for the rest of his life, settling into the peaceful surroundings and drawing new inspiration from the agricultural life and landscape around him. Already familiar with Troyon and Diaz from his Paris days, Millet’s great, lifelong friendship with Rousseau developed in Barbizon from the early 1850s. Millet and his wife cared

for Rousseau during his final illness and Millet is buried next to him in the cemetery at Chailly.

The seminal paintings for which Millet is most celebrated date from after this move to Barbizon and include The Sower, 1850 (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) of which there are several variants, The Gleaners, 1857 (Musée d’Orsay) and The Angelus, 1857-1859 (Musée d’Orsay). All three treat the figures of labourers with quiet deference, and allow them to fully inhabit the paintings, taking their natural role in the centre, as they did in the reality of rural life. Millet chose to represent rural labour rather than an idealised portrayal of life in the countryside, and it was

this which was disconcerting for those who favoured the established order of subjects. A peasant sowing seeds, striding across a field with purpose and evident physical strength, in a

composition which gave him stature, could either be seen as recognising the dignity of the working man in keeping with the Revolution, or distorting the accepted hierarchy of reserving such esteem for those of noble birth or of legend.

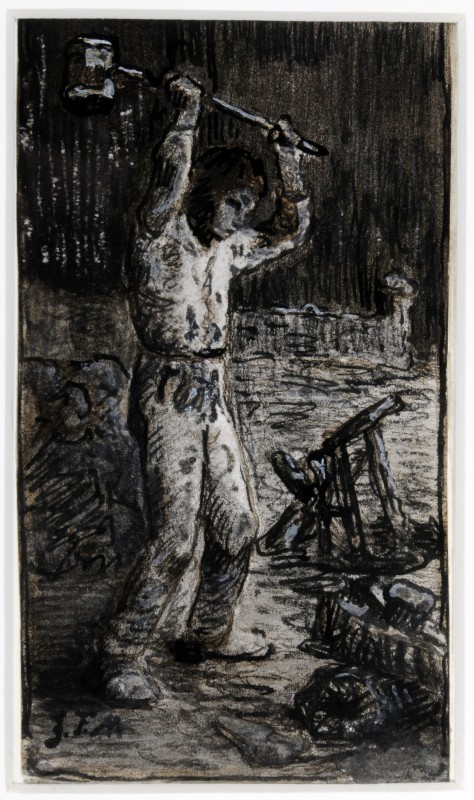

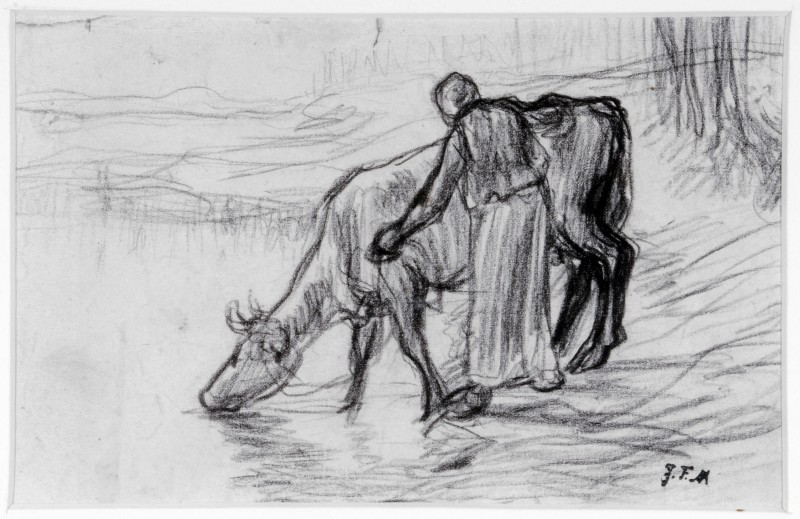

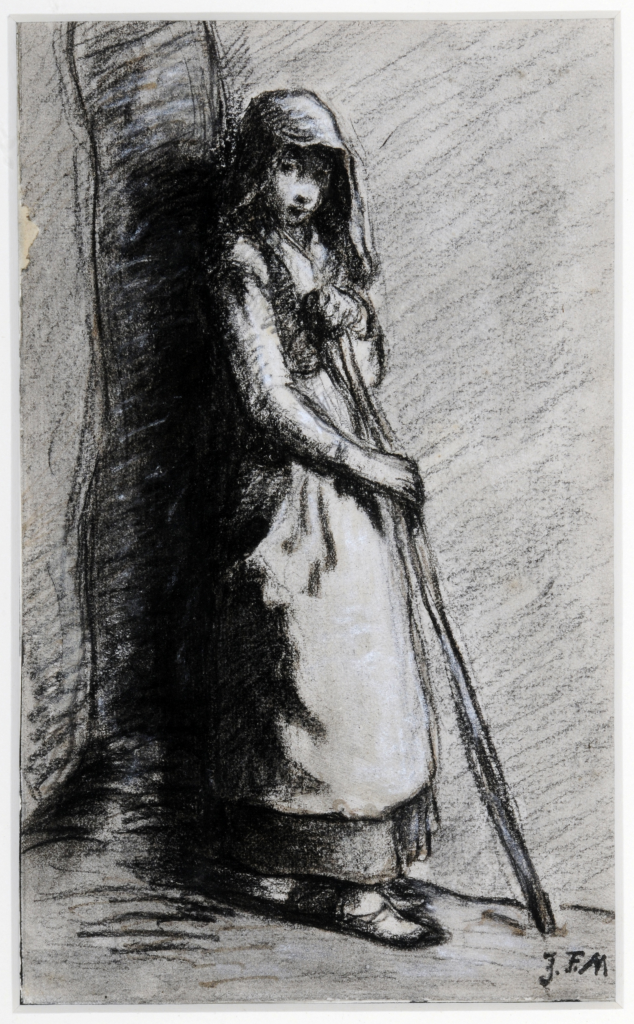

The three drawings by Millet in the exhibition were all gifted to the Cooper Gallery by Sir Michael Ernest Sadler and have all been found to relate to finished oil paintings or other drawings. Prolific as a draughtsman, Millet seems to have been constantly drawing, and these

come in different sizes, on different papers and in different media. The largest collection of existing drawings by Millet (almost 600) is at the Musée du Louvre in Paris, part of the Musée d’Orsay permanent collection. What is fascinating about this collection is that it doesn’t consist solely of ‘finished’ or even ‘half‐finished’ drawings. Many are recognisable as sketches towards

later works, but some are sketches of a few seconds on small scraps of paper. As such they provide an amazing insight into Millet’s work and the subjects he observed which later appeared in his major paintings.

The Shepherdess is linked to works in The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge and the Burrell Collection, Glasgow Although the Cooper Gallery drawing is not dated, the oil painting at the Burrell has 25 April 1849 on the reverse. This was before Millet’s move to Barbizon, and the difference between this portrayal of a girl and his later paintings of figures working in the landscape is pronounced. In The Shepherdess at the Cooper Gallery, the young girl is looking at the viewer, one can see the expression on her face and, although barefoot, the Burrell painting

A Shepherdess shows her with clean, bright clothing in good condition.

Light & Soul: Early Impressions of The French Landscape Exhibition

The painters of Light and Soul drew inspiration from ancient forests and valleys, contemporary life in the landscape and the shifting light over rivers and seas. The exhibition brings together 17 exceptional artists including Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, Camille Corot, Rosa Bonheur and Eugène Boudin. All were pioneers who experimented with subject matter, style and technique and whose influence shaped the work of generations to follow.

You have until 7 October 2023 to see the exhibition but we have also created an online exhibition where you can watch videos, listening to an audio guide, read more blogs and more.

Have you read our recent blogs?