Barnsley Archives are currently cataloguing the archives of Lancaster and Sons, long-standing Barnsley estate agents and auctioneers. This has uncovered some fascinating and previously forgotten stories. One of these is the Mallinson’s rope walk dispute on Eldon Street in 1881. The story shines a light on Barnsley’s little-known rope industry. It also provides a unique snapshot of the early development of Eldon Street, from a new road on the edge of the town in 1840, to a valuable and contested town centre location, over a period of just 40 years. Archivist James Stevenson tells us more.

First things first – What is a ropewalk? If you already know, you can congratulate yourself and skip this paragraph. However, if you don’t already know, rope-making is a highly skilled trade in which long strands of natural or synthetic fibres are twisted together to form a rope. This requires long, straight, narrow premises called ropewalks. In its simplest form a ropewalk can be a stretch of ground in the open air, but more often there is a shed or structure of some sort to protect the manufacturing process from the elements. There are some surviving ropewalk buildings in Britain, including at Chatham Dockyard on the River Medway in Kent, which is still producing rope on a commercial basis, and the former rope manufactory at Barton on Humber, which is now The Ropewalk arts centre.

It’s no coincidence that both these surviving buildings are on major rivers. In the days of sail the Royal Navy and commercial shipping required immense quantities of rope, and rope walks were often associated with ports and maritime cities. However, as the Industrial Revolution progressed, other industries – including the mining industry – also required rope, and so Barnsley too acquired its rope makers.

One of these was, appropriately enough, located on Roper Street, which used to run between Westgate and Churchfield (now covered by the Magistrates’ Court). But the most central of the Barnsley rope works was run by the Mallison family on Eldon Street. It was this central location which eventually led to a high-profile dispute between the family and the Barnsley Corporation.

The photograph above shows the part of Mallison’s premises that faced the street in the late 19th century. Behind Mallison’s shop, and out of view of the camera, was the long, narrow building that housed the rope-walk.

Another view of the area comes from the Ordnance Survey map of 1889. The ropewalk itself is clearly marked, along with an adjoining building at the Eldon Street end, in the shape of an inverted-L. This is the single storey building which sits below the John J. Mallison sign in the previous photograph.

Immediately north of the inverted-L on the map is a tiny, wedge-shaped building, which is the shop with the barber’s pole next to Mallison’s in the photograph. The two larger buildings to the north of the wedge on the map are the three-storey houses and shops in the photograph (Bailey’s and Lockwood’s).

Here is a modern photograph taken from exactly the same spot. The plain wall with the taxis in front is the site of the two three-storey buildings, ‘Welcome to the Glass Works’ is the site of the barber’s shop, and the windows of the Salt House bar and restaurant are the site of Mallison’s shop.

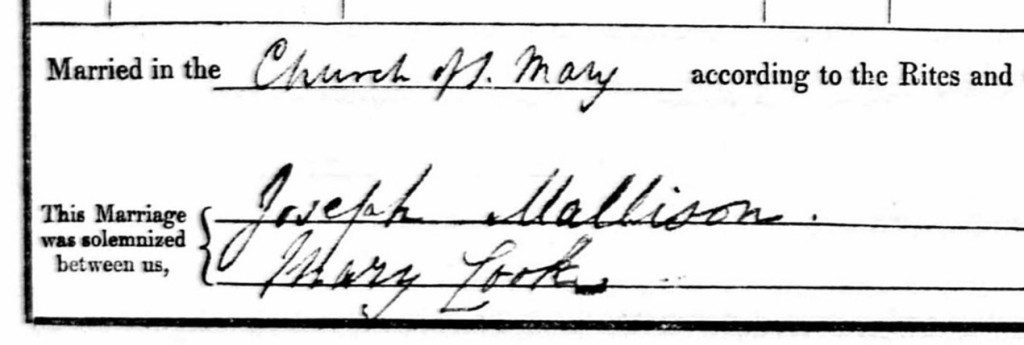

The Mallisons were an old-established family of rope makers. The sign on the Eldon Street premises proudly claimed that the business was established as long ago as 1759. By the early 1850s, it was run by John Mallison and his son Joseph, although they were at that time only tenants of the property. However, after the death of their landlord, John Clarke, the plots over which the ropewalk lay were offered for sale and were bought by John Mallison in September 1854. Four years later, in September 1858, his son Joseph was married at St Mary’s church to Mary Cooke. Joseph and Mary soon started their own family, welcoming Lucy Ann, Mary Jane, Florence, Elizabeth, Lily, and their first (and only) son John Joseph Mallison, who was born in 1868.

In that same year, 1868, problems started for the Mallisons in relation to their premises on Eldon Street. The Midland Railway, acting under an Act of Parliament which granted it powers of compulsory purchase, required the eastern end of Mallison’s property to build the railway arches to carry the new Cudworth and Barnsley branch and to create Midland Street.

The negotiations for compensation from the Midland Railway were later summarised by the leading Barnsley estate agent, auctioneer and valuer Edward Lancaster. The sum arrived at, £2,000, was not based solely on the value of the land itself:

“… our Claim was based principally on Trade Compensation. The shortening of the Rope Walk totally destroying the Trade for Colliery Pit Ropes. The Profits on which Branch being estimated by Mr. Mallison to be 2/3rds of his whole Profit.”

The Bank of England’s official calculator suggests that £2,000 in 1868 would be the equivalent of approximately £186,000 today. Nevertheless, despite this reduction in the lengths of rope that could be produced, and the subsequent loss of colliery trade, the business continued. John Mallison died in 1870 and his son Joseph became head of the firm. In the census of the following year Joseph is described as ‘Ropemaker (employing 3 men & 3 boys)’.

Unfortunately, in 1878 the family suffered another major misfortune when Joseph Mallison died, aged only 52. His son John Joseph was only ten years old, so Joseph’s widow, Mary, took over control of the business. This situation was not as uncommon as might be supposed, as discussed in our previous blog on women business owners of Eldon Street

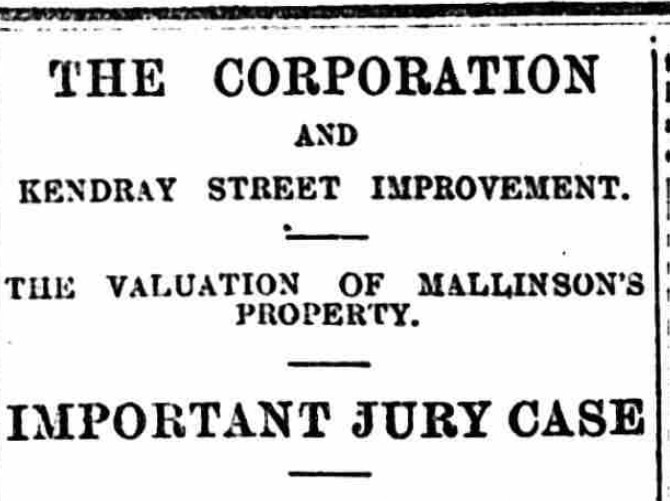

In 1881 came another dispute over the ropewalk and, once again, it was the business’s increasingly central location that caused problems for the Mallisons. This time it was Barnsley Corporation (the town council) which made an order for the compulsory purchase of the whole of the Mallison property. However, this time agreement on how much compensation the Mallison’s were owed for this could not be reached and the only solution was a public hearing before a specially-summoned jury to agree a sum independently. Our main sources of information for the hearing are the archives of the firm of Lancaster & Sons, estate agents, auctioneers and valuers, which are currently being catalogued by Barnsley Archives, and an article in the Barnsley Chronicle.

It should be noted that, at the time of the dispute, the premises facing the street looked a little different to the photograph shown above. The three-storey buildings were then simply a pair of private houses and had not yet been converted into shops, while the right-hand end of the single-storey block, with the blank wall, was then a newsagent’s shop.

The hearing took place over two days, opening on Thursday, 7 April 1881, at the Town Hall, which at that time was on the corner of St. Mary’s Place and St. Mary’s Gate. The presiding officer was Mr. W. Gray, Under Sheriff of Yorkshire, and a jury of twelve was selected from a panel of twenty, all of whom were gentlemen, manufacturers or tradesmen from towns other than Barnsley, to avoid them being influenced by local connections.

Barnsley Corporation was represented by a Queen’s Counsel, Mr Shaw of Leeds, who was instructed by the Barnsley Town Clerk, Mr Horsfield. Mrs Mallison had engaged her own Queen’s Counsel and barrister, instructed by the local solicitor Mr Dibb, of the firm of Dibb, Raley and Clegg. The Chronicle was certainly accurate in referring to the hearing as a “costly process”.

The case focused on several points, the first of which was the development of Barnsley itself which “had for many years been undergoing great and very proper improvements, at the hands of the enterprising gentlemen who controlled it, who were evidently alive to the responsibilities thrown on them by the rapid growth of the town”.

As we have seen, Mrs Mallison had taken over the running of the business after her husband’s death and in the 1881 census, which had been taken only a few days previously, she described her occupation unambiguously as ‘Rope and Twine Maker’. Nevertheless, her Q.C., Mr J. C. Day, was quite happy to portray her in a more stereotypical light, that of the poor defenceless widow, as he addressed the jury: “He regretted, on behalf of his client, that the Corporation had found it necessary to take this little property and he would tell them why. This property was the sole means of existence to his client, Mrs Mallinson and her children… The children left by Mr Mallinson when he died were four daughters and a son, now 13 years of age, who, with the widow, were now depending upon the business for support.”

There was a consistent discrepancy between how the Mallisons spelled their own name, and how the Corporation and the newspaper spelled it. The family themselves always used ‘Mallison’, both on their signboards and in their signatures, whereas the Corporation and the Barnsley Chronicle consistently mis-spelled it as ‘Mallinson’. Perhaps there was very little distinction when the name was spoken aloud.

As Mr Day continued his address to the jury, even he conceded that the location of the ropewalk had, as the town developed around it, become unsatisfactory: “…there were several ways in which the property might be dealt with. He thought they would agree with him that, having regard to its situation, this property should not be dealt with as a rope-walk. No one buying the property would think of carrying on a rope-walk upon it… It was almost amusing to find a rope-walk close to the centre of the town.”

The point of this comment was that he wished the jury to consider not only the compensation value, but also the potential development value of the property, “Eldon Street being one of the most important streets in the town.” He then introduced a scheme for the proposed redevelopment of the property, with the pair of three-storey houses to be converted into shops and the single-storey block pulled down and rebuilt more substantially. It was on this basis that all the succeeding arguments as to potential value were based.

Various local witnesses were then called, including architects, builders and valuers, who gave varying evidence about the state of the market for housing and commercial properties in the town and the costs and projected profits of the proposed alterations. Among the more interesting points made, was that Eldon Street had a fashionable side and an unfashionable side – the better side was the opposite one, containing the Public Hall, a theatre and the better shops. However, one of the witnesses stated that “our side is improving.”

Among the expert witnesses called on the second day were Edward George Lancaster and his father, Edward Lancaster, both of the firm of Lancaster and Sons, auctioneers, valuers and land agents. They had been engaged on behalf of the Corporation and much of their evidence dwelt upon the difficulties of trade and of unlet commercial properties.

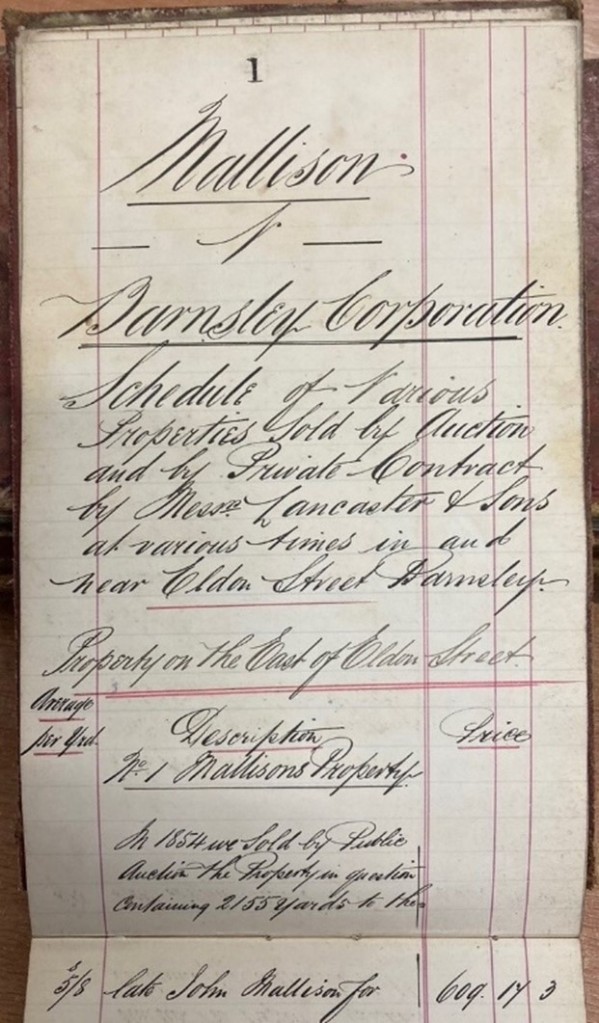

Apart from the Chronicle report, there are further details of Lancaster and Sons’ evidence in the Valuation Book which they compiled ahead of the hearing. The firm had not only arranged the sale of the Eldon Street property to John Mallison in 1854, and negotiated the compensation from the Midland Railway in 1868, but had also been responsible for the sale of many of the neighbouring properties over the years, on both sides of the street:

“Hawksworth’s. In 1873 we sold to the Public Hall Company 2,292 [square] yards of land without buildings for £3,150.” “Till’s Warehouse. In 1876 sold site and warehouse by public auction for £3,950 and ruined Hindson the purchaser and Till the builder”.

They also confirmed the discrepancy between the two sides of Eldon Street: “For business purposes the value of property on the East side of Eldon Street is not worth so much by 33 per cent as on the West. Fully two-thirds of all traffic to and from the … stations passing on the West side of the street.”

Lancasters’ valuation book also gives us, though brief, our best written description of the rope-walk itself: “2 covered sheds supported by iron & wood pillars. Stone-built store house with dressing room over. Back yard & garden, also back entrance from Midland Street, enclosed.”

The Barnsley Chronicle reported that Mr Shaw concluded “that the Corporation was wishful that Mrs Mallinson should have a liberal but not an excessive compensation.” After all, the Corporation was answerable to the ratepayers for public money.

Mr Day, for Mrs Mallison, “proceeded to address the jury on behalf of his clients, in a speech which occupied nearly an hour and a half. The Under-Sheriff then briefly summed up, and at twenty minutes to four the jury retired to consider their verdict. After about an hour and twenty minutes they returned to Court, when the Foreman announced the verdict – £4,750.” According to the Bank of England’s official calculator, the present-day equivalent would be £475,000.

Both sides accepted this valuation and the Corporation acquired the premises from Mrs Mallison. However, until such time as the Corporation was ready to develop the site, they leased it back to the Mallisons.

After the drama of 1881, things settled down. The Mallisons remained as tenants of their former property, John Joseph Mallison grew up and took over the management of the business and his mother retired to a house on Sheffield Road. The scheme discussed at the 1881 hearing was gradually adopted, with the pair of houses being converted into shops and the single-storey block eventually being demolished and rebuilt, in about 1907.