Following on from Catherine Roebuck’s last blog, here’s part two of Trouble at T’Mill, stories about life at the mill brought together as part of #WorsbroughMill400 celebrations, a year long project funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and supported by Barnsley Museums & Heritage Trust

Fires and Explosions – it’s surprising what dust can do

Mills through time and even still today, in the right circumstances, could have fires and explosions. These had two main causes. Firstly, when grinding the grain, the flour produced is combustible if ground finely enough. If the concentration of airborne flour dust is just right, and is in a confined area, a simple spark could cause a large explosion. Secondly, the new mills would have an engine, with a coal fired boiler. This fire could ignite the dust, or the coals could crackle and pop, flying hot fleck out of the fire on to nearby sacks, paper bags or other ignitable materials.

I could not find any stories about fires at Worsbrough Mill, but we know that at least one of the millers had experienced a mill on fire.

John Watson had gone into partnership, at the start of his career as a miller, in about 1830. Just as things were going well, disaster struck. On 26th February 1842 the mill occupied by ‘Jackson & Watson’ at Burton Bridge was destroyed by fire. We can’t find any more about this incident, but by 1851 the mill was again a thriving business. Jackson and Watson also farmed 23 acres of land and employed 7 labourers.

While trying to find out about the experiences of the millers of Worsbrough, I had to research other local mills. The next story is about a Steam Flour Mill by the Canal at Elsecar, but it will give an idea of what millers could witness.

It was a Saturday evening in January 1874 when an alarm was raised. The Flour Mill was on fire. The three storey building stood between the road and the canal.

At 7.30pm Charles Swinbank was passing the Mill, worked by Mr Ellis Williamson. Ellis Williamson had married in 1871 to Sarah Stansfield. He was only a young man and Elsecar Steam Mill was his first venture on his own. They moved there in 1873 and within six months disaster happened.

Charles saw a light shining through a window and alerted the local police. The officer broke open the door and found the fire raging in the screening room, on the second floor, immediately over the engine, and it quickly spread to the roof. A telegram was sent to Barnsley for the Corporation engines, and a rider was sent to Wentworth Woodhouse for the fire engines kept there.

In the meantime, the local people, officers and the miller assembled and worked to clear the mill of grain, flour and anything that could be removed that would feed the fire.

Two hours after the fire was spotted the first engine from Wentworth arrived, followed by a second engine. They drew their water supplies from the canal, which ran just behind the mill. The two engines from Barnsley arrived at 9.45pm. It took until midnight to get the fire under control. The Wentworth engine continued to dowse the embers until 10am on Sunday morning. The fire continued to smoulder until Wednesday.

The storerooms were saved except for the roof, and the engine only had minor damage. Much machinery was destroyed, and Ellis lost a considerable amount of stock. The occupier, Mr Ellis Williamson suffered losses estimated at £2,000. Earl Fitzwilliam who owned the building had damage costs for the machinery and building of around £2,000 as well.

Ellis rebuilt his business and remained at the Elsecar Steam Mill until about 1881. He lived in the house attached to the mill and his first 4 children were born there. After leaving the mill, Ellis became a Corn Merchant in Leeds and died a wealthy man.

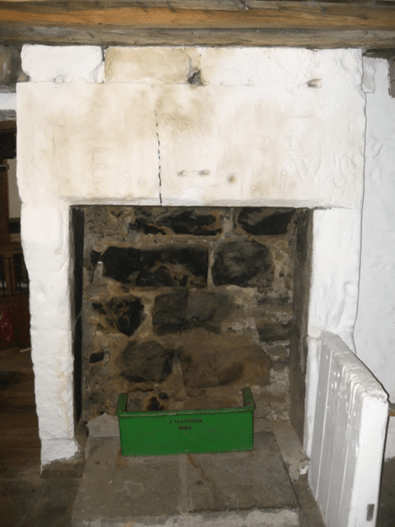

Worsbrough Mill also had a house attached and it was lived in up until the 1750’s, when the new house was built on the terrace above the mill. The right hand half of the Old Mill would have originally been the house and had 2 fireplaces. One on the ground floor and one on the upper floor.

The size of the fireplace was quite large and would have been in the main room where all the cooking would have taken place. Nowadays this space is one big open room with 3 sets of millstones, but originally the room would have been split in two, with a wooden partition wall, separating the fireplace from the explosive dust on the milling side. Many mills were destroyed by fire, but our 400 year old mill was spared this, even though it had open fires, coal fuelled steam engine and explosive flour dust. It has survived.

Changing landscape – Reservoir, canal, waggonway, floods and the new road

The landscape in the early years would have remained the same. The mill served several small farming hamlets. But by the 1790’s this began to change.

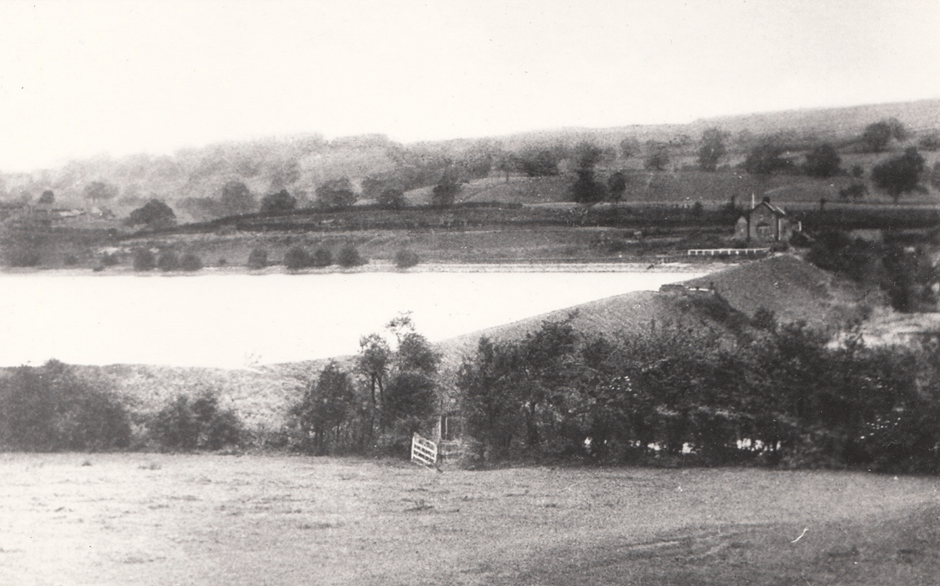

With the beginnings of industrialisation and population growth, the need to get products away to markets further afield became essential. This led to the construction of the reservoir behind the Mill, which was built to supply water for the Worsbrough Branch of the Dearne and Dove canal system. The navvies started the construction in 1798.

William Shaw was the miller at the time. He witnessed the terrible disruption to daily life. Dozens of wagons constantly coming and going, bringing stone for the dam wall and removing earth. Hundreds of navvies and their families moved into the area, all needing to buy flour. This meant more work for the mill, but the water supply would be constantly interrupted by the building work. William would also have witnessed several of his fields disappearing under the rising waters as the valley flooded. The Canal opened in 1804.

There was a positive to all the upheaval as it brought new opportunities to Shaw’s Mill. The possibility of bringing wheat up the canal and taking flour further away to new markets. All of this led the mill to change from being a Toll Mill and becoming a Merchant Mill.

When William Shaw took over running the Mill around 1782 it would probably have been run as a Toll Mill. Customers brought small amounts of grain to the mill for grinding and instead of money changing hands the Miller would have kept 1/16th of the customers milled meal.

The population of Worsbrough started to increase with the arrival of the canal. Ironworks, coal mines, glassworks, boatyards, gunpowder mills, and several other industries sprang up along the valley. With this influx of people to the area, Shaw’s Mill adapted quickly becoming a Merchant Mill. Buying in grain and selling direct to the new growing population and later to local bakeries. Ann and William Shaw became quite wealthy during this period.

In the 1920’s another milling family was affected by the building of a reservoir. George Steel and his family were forced to leave Broomhead Mill, near Bradfield.

The city of Sheffield was growing fast and the need for drinking water had increased as the population expanded. New reservoirs were planned at Broomhead and Morehall in the Ewden Valley and should have come under construction in 1913. Broomhead Mill was to be flooded, but the First World War postponed the plans, and the family stayed there for a while longer. But in 1916 the navvies moved into the Valley, and construction began. The reservoir was officially opened in 1929, but the family moved out in 1923 as the Valley flooded. The Steel family moved to Worsbrough Mill, which had survived the building of its own reservoir.

Waggonway

The Waggonway changed the landscape again for the Worsbrough Miller. It was built around 1830 and extended from the canal head, along the southern edge of the reservoir, passing the back of the mill. Just below Rockley Old Hall there was a junction with one branch going to Silkstone Main Colliery and the other to Pilley Hills Colliery and Ironstone Mines. It was used to transport coal and iron stone from the mines to the canal, where it would be loaded on to the boats.

The track was laid with parallel rails spiked into stone blocks. Some stone blocks can still be seen under the hedges beside the path, which runs along the mill race. The wagons were pulled on these rails, by horses on the level sections and by stationary engines on the inclines.

Several stone blocks which were retrieved from the hedge bottoms around the Country Park and set up outside the Mill House.

By the early 1830’s John Saville was the Miller, and he farmed land around the reservoir. He lost a strip of land along the edge of his fields for the building of the waggonway. But in the Edmunds Estate Account on 24th October 1834, he is compensated for this lost.

J. Saville for Railway 2 years 7 pounds

To get to his fields John would have to cross the rails and a line also crossed the road he used to get the grain to the mill. For a time, the ponies who pulled the tubs of coal down the waggonway to the canal, were stabled at Worsbrough Mill, and the mill also supplied oats for their feed.

The line was eventually sold to the South Yorkshire Railway and the main traffic continued to be coal and iron. The line was finally abandoned about 1920 and the ironwork removed. The stone blocks were thrown into the hedge bottoms or used in walls of nearby buildings.

Floods

In 2010, miller George Steel’s granddaughter Elizabeth, in her 70’s, visited Worsbrough Mill. She told a story about her grandmother’s funeral in 1932. She remembers visiting the mill with her mother Winnie, when she was about 5 years old. The family were supposed to travel to Bolsterstone for Grandmother Elizabeth’s funeral, but Worsbrough Reservoir burst its banks and water flooded around the Mill, trapping the family. There are photos of the flood.

This wasn’t the first time the reservoir had burst its banks or over flowed. From the very beginning flooding was always a problem.

During the construction of the reservoir, it burst its banks on several occasion. The first breach in the Reservoir Head was on 15th December 1802. A second breech happened on 19th December 1803.

Before the first breech a report in January 1802 suggested “It should be recorded in the minutes of the Company as a general order for further security against accident, that in heavy rains, when there is a probability of a flood it should be anticipated by drawing down the reservoir 5 or 6 feet or more or less as experience may direct.”

After several more breeches, in January 1804, a 6-foot Culvert (now called the deep draw valve) was created out on the east side of the Reservoir Head to allow the drawing down or lowering of the reservoir before heavy rains.

In June 2007 I witnessed the floods for myself. It had been raining for days when I arrived at work. The rain was heavy, and we walked the reservoir to see how bad it was. Through the day the water rose, and we had to close the Country Park. Several paths had turned into rivers, the inlet stream from Brough Green Brook had flooded the path to waist height.

Three feet of water was coming over the two spillways on the dam head, at its height and was being directed into the River Dove, which in places was less than four metres wide. The Sports Ground was flooded and as it narrowed to go under Worsbrough Bridge, which carries the A61 main road to Barnsley, the water was force over the top, slowing and eventually stopping traffic. The Mill yard was flooded, and the water reached the Mill door but luckily did not enter.

It was down river that the damaged was done. As the water reached Darfield the river burst its banks and flooded dozens of homes. The main damaged to the Country Park was a bridge into the woodland, which was lifted off its base and deposited on the bank a few yards further down river.

Over the next two weeks the water went back to normal, and we got a tractor from a local farm to drag the bridge back into position, as it wasn’t too badly damaged. The ground was still saturated, then the rains came again. The second flood was slightly worse than the first, Darfield was flooded again, and our refitted bridge went downstream in pieces.

In recent years new staff have come and when it rains, they see the water in the river rising. They start to worry, and I just say, “that’s nothing, you should have seen it in 2007”.

The River Dove overflowing and flooding the road at Worsbrough Bridge and The Waggonway Path at the side of the reservoir.

The New Road – A61

This little corner of Worsbrough underwent significant change during the 1840’s, when the main highway from Sheffield to Wakefield was diverted. The original road passed through Worsbrough Village, travelling down the steep hill to cross the River Dove at Worsbrough Bridge, before climbing the hill to Barnsley.

The Miller had a lane which joined this old road. As you walk from the mill down to the car park, a small path goes off to the right. The Miller would have brought grain on his cart, from the local farms and taken the flour back up to the local village along this path.

The original road was described in the Doncaster Quarter Sessions on 11th Jan 1841. The Quarter Sessions were local courts that met four times a year to handle less serious criminal and civil matters, like licensing and highway supervision.

“….. Turnpike road from Wakefield to Sheffield both in the said Riding at or near Worsbrough Bridge in the township of Worsbrough aforesaid, leading to and through the village of Worsbrough and ending at Birdwell Common …..”

This Old Road was said to be dangerous.

“….. highway between the said Village of Worsbrough and Worsbrough Bridge aforesaid, was for the most part a narrow and crooked road, consisting entirely of a very steep and dangerous hill, where serious accidents had several times happened …..”

The route of the New Road was also described in the Doncaster Quarter Sessions.

“….. Birdwell Common in the same Township at or near to the place where the new diversion of the said Turnpike Road commenced and proceeds thence towards and communicates again with the said Turnpike Road near Worsbrough Bridge aforesaid was said highway was of the length of two thousand and sixty eight yards and of the average breadth of thirty three feet and six inches …..”

The new diversion went around the side of the hill and avoided Worsbrough Village entirely and was seen as a safer option.

“….. new diversion of the said Turnpike Road was more commodious to the public than the said highway, because such new diversion of road was of an equal and regular width, and was made wider than the quarter part of the said highway and was free from abrupt and dangerous turns and was of a gradual and regular inclination …..”

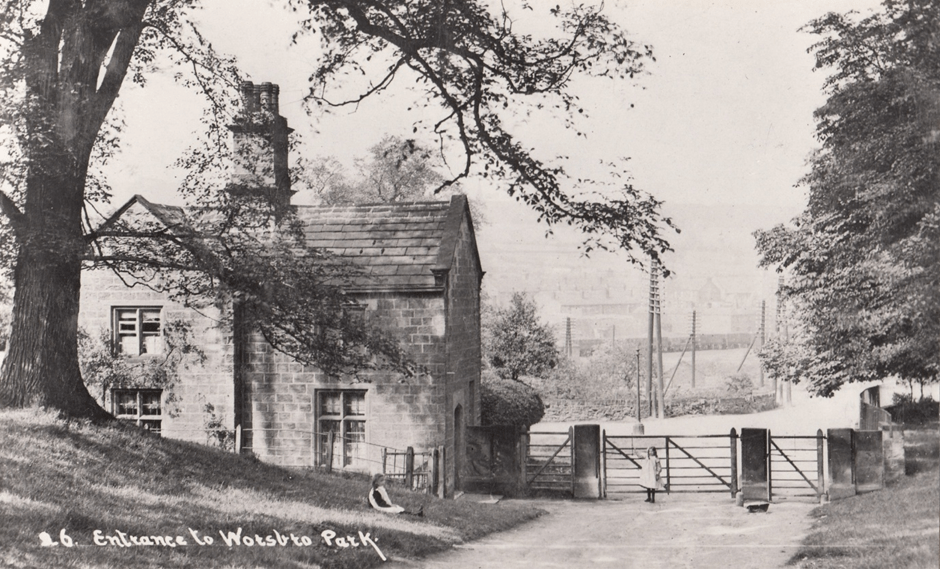

When this new diversion was built the old highway was to be stopped up and gated as part of the parkland of William Bennet Martin Esquire. It was seen as “unnecessary as a common public highway” and the Trustees of the Turnpike Road would, “therefore abandoned the future repairs and maintenance” of the old road.

In April 1841 permission was granted for the new diversion and building commenced. It is now part of the A61.

The Worsbrough Miller had several fields in which he grew his own crops, these field were long strip like the old medieval fields. The new road cut these fields in half. Instead of having long strip that he could plough with a horse, he ended up with a short bit of field below the road and a short field above the road. He also lost the land the road ran on, a strip about 10 metres wide from the middle of his fields.

Throughout the time the road was under construction the miller would have had difficulty getting to his fields. The hillside was cut into and the earth embanked on the lower side to give a flat base from the road. It would have taken several years with barrows, picks and shovels, to complete the work.

But the new road would make it easier and safer to transport the grain and flour. Opening new markets. The miller’s business thrived, and he relied less on growing grain himself, as the mill become busier, he brought grain from other farms and became a Merchant Miller.

For me, researching all these stories have given a greater understanding of the struggles in the lives of our Millers. From floods, robberies, changing landscape which brought both hardship and a boom in business, and also loss of life. These accounts bring their world to life and keep alive their forgotten stories.

Have you read our recent blogs?

Subscribe to our blogsite to have new articles sent direct to your inbox