Continuing our year long celebration of #WorsbroughMill400 which has been made possible through funding from National Lottery Heritage Fund and support by Barnsley Museums & Heritage Trust Catherine Roebuck (Visitor Services Assistant) has been delving into the history of the 400 year old mill.

‘Trouble at T’Mill’ is used nowadays as a humorous phrase to refer to a problem, especially at home or at work.

But the saying has been used for centuries to describe a situation where there is chaos or confusion, especially in a factory setting. The phrase suggests the idea that these mills were often plagued by various problems such as machinery breakdowns, labour disputes, and accidents. The phrase is spoken in the accent of northern people, especially Yorkshire, where the word ‘the’ is often not fully pronounced.

Worsbrough Millers had hard lives, and we will cover some of the troubles and strife that have transpired in their time at Worsbrough Mill. All these stories are from documented facts from newspapers, court records, census records, and many other documents of the time.

Robbery – The cost of our daily bread

When the harvests failed due to drought or excessive rain, the people in the surrounding area would go hungry. This became a time of conflict for millers. People would try to steal from the mill as they knew flour was stored there and that is why we have bars on the windows of the oldest part of Worsbrough Mill.

In January 1814 a case of stealing came before the Quarter Court Session held at Doncaster. A small farmer of Worsbrough was charged with stealing meal from Worsbrough Mill on the 1st day of May 1813.

Thomas Wood and his servant lad, George Conway went to the mill on a Saturday evening. George had only been working at Wood’s farm for about a fortnight, when his master ordered him go with him to get a met of hinder ends ground to feed the pig (hinder ends – the light stuff blown off when threshing).

As they were walking along, Thomas Wood said “George, I’ll take old John Wagstaff (meaning the miller’s man) into the top chamber and keep him cock-a-spell whilst thou must get a little as we shall not have enough to serve till winnowing again.”

When they arrived at the mill, old John Wagstaff was not in. The miller’s lad was watching the machinery, he was also called John Wagstaff, being old John’s 14 years old son. Thomas and young John took the corn to the stone floor above and put it into the hopper to grind it. Thomas left young John upstairs and returned to George and said, “Old John Wagstaff is not in – we have a nice chance”.

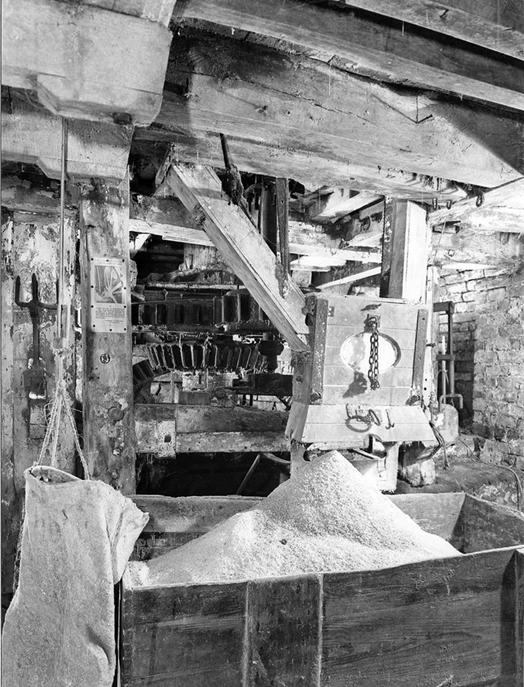

A Meal Ark on the bagging flour, Worsbrough Mill

In the meal ark was a quantity of barley meal which was put together at one end, leaving the other to receive the meal grinding from the hinder ends. Young John was with them, but on the ringing of a bell, indicating that the hopper was nearly empty, he ran upstairs to stop the mill. Farmer Thomas took the sack and holding it open said, “George, put some of the barley meal in”, which George immediately did. Thomas then filled the sack up with his own meal and left. After carrying the sack on his back for a short distance, he gave it to George to carry, saying, “Damn me George, we’ve got a rare lump this time. It’ll serve the pig a good bit”.

Several witnesses to the theft were called and travelled to Doncaster to give their statements. Witnesses included, Old and Young John Wagstaff – millers, George Conway – farm boy, Elizabeth Hammerton – widow, small farmer and owner of the stolen barley meal, and six other local men. Ann Shaw the owner of the mill business didn’t travel to Doncaster for the trial. She was in her 70’s and too old to travel on the rough and dangerous roads, in the cold weather of January 1814.

Thomas Wood confessed to the crime and was ordered to be confined till the rising of the court.

Machinery – where is the big red button?

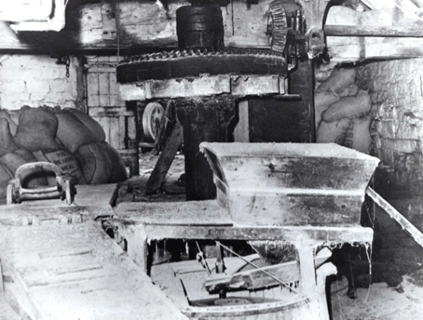

Working with mill machinery can be very hazardous. Unlike modern machinery, which have big red, power cut off buttons, the old water mill can only be stopped if you go up to the mill pond and close the water off, but this can take several minutes.

This next story was told to me on my first day working with the machinery, to stress that the dangers are still the same as they were in the 19th century and we must work in line with the risk assessment we have in place. Not something you want to hear when you start a new job. I investigated the story and found a very detailed coroner’s report and newspaper articles of the incident.

In April 1881 Worsbrough Mill was managed by John Watson. He employed an Assistant Miller called Thomas Heppinstall and a Mill Carter, George Coope. It was a Monday morning, Thomas arrived at work at about half past six and Mr Watson gave him his directions for the day, and they worked together until 8 o’clock. Mr Watson left, and Thomas continued alone.

Thomas Heppinstall was 39 years old and a native of Grimethorpe, near Shafton. He was living in Red Lion Cottages, behind the Red Lion Inn, which was only a few hundred yards from the Mill. He had a wife Martha and 7 children, the eldest of whom was about 15 years of age and the youngest about a year old. Thomas had been at the mill for more than 11 years and was a competent miller who knew his job well.

George Coope, Mill Carter had brought some oats to the mill and had been helping Thomas, but shortly before 2 o’clock he went to another part of the mill for a few minutes, to move the oats. About five minutes afterwards he heard a cry, “Stop the machinery”. George went back to where he had last seen Thomas and could just observe his back. He looked through an opening and called “Tom” three or four times, but there was no answer. He then opened a door outside the mill and saw Thomas on his knees under a large cog wheel. It would be almost six feet from where George supposed he fell in, Thomas must have been taken around by the wheels, which move in a reverse direction. He was at a loss to know how Thomas got through the opening.

George ran for help from a wagon passing down the colliery tramway, behind the Mill, he called the driver, George Howett, over to aid him. He then ran to the Red Lion Inn to get someone there to fetch a doctor. On returning the two men got Thomas out from under the Pit Wheel. There was a good deal of blood on one of the cog wheels near the wall and a good deal more on the floor where he was laid.

They got Thomas onto a cart which was brought from the Red Lion Inn to transport him home.

On arriving home, his wife Martha, who had heard he was injured was waited for him. He spoke to her saying, “God help thee and thy children” and then said, “God help me”. He died about half past 2 o’clock.

Ruth Crossley had arrived just before he died. She had been sent for to help patch Thomas up and nurse him. Some women within the community would help nurse the injured people and then lay out the body if they died. Ruth said it was hard to undress Thomas ‘His body was so badly broken up.’

On Tuesday Mr Thomas Taylor, Coroner arrived at the home of Mrs Parratt, landlady of the Red Lion Inn. This is where many local Coroner Court hearings were held. The Coroner and 12 jurors from the local area sat and heard all the evidence from the witnesses and examined the body which was on display in the Inn.

The injuries on Thomas’ body were serious. Both his legs were fractured in several places; his head had been damaged with large gashes where the hair was missing. His abdomen was seriously crushed, there was a hole in his back which you could fit both hands into, and many other smaller fractures, cuts and bruises.

The Coroner summed up the evidence for the jury and reminded them that they did not know why or how the deceased had gone amongst the machinery. The jury returned a verdict that the deceased died from injuries accidentally received.

Thomas Heppinstall was buried on 27th April 1881, in the graveyard across the road from St. Mary’s Church in Worsbrough village. He was 39 years old. He has no headstone.

His wife Martha Heppinstall was left alone to raise their 7 children. She would have struggled as only one child was old enough to work. Her eldest son John, at 15 years old, went to work in the local mines. Over the next few years Martha took in lodgers to help pay the rent. By the next census in 1891 Martha had moved her family to South Hiendley. Her husband’s family lived around the area and could help her. As the children left school, the boys went to the miners, and the girls became servants. They all survived and although Thomas Heppinstall would never meet them, he had 39 grandchildren. Martha never remarried and died in 1910, aged 67 years.

Unrequited Love – A sad tale

I found out about this true story while doing a little lunch time reading of a coroner’s record book from the 1860’s. But it was when the girls working in the Miller’s Tearooms said they often felt cold or that someone was watching them, as they passed from the corridor to the kitchen. I proceeded to tell them the following story and for several days afterwards they were a little jumpy.

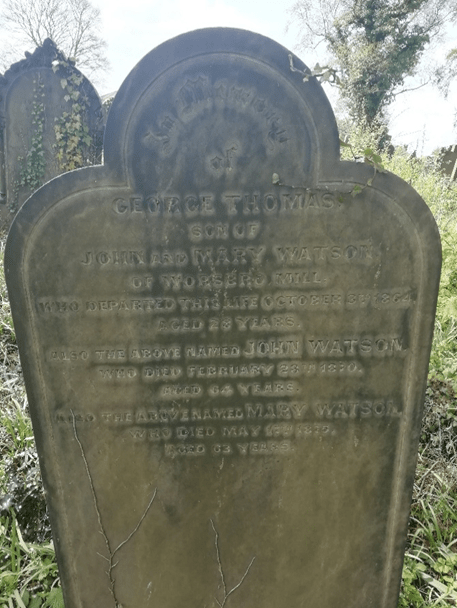

The story starts on a Sunday afternoon in October 1864. A young man named George Thomas Watson left home and walked to Barnsley. George was 28 years old and superintended the business of his aged and blind father, John Watson of Worsbrough Corn Mill.

Earlier that morning, George got up at 7 o’clock and ate his breakfast as usual, remaining at home all morning. After eating a hearty dinner, he left about 2pm, saying he was going to Church, returning for tea at 5 o’clock. He only stayed for 15 minutes and went out again without saying where he was going.

George’s mother, Mary Watson, said later that he had been “very low spirited for the last fortnight,” but apart from a cough which he’d suffered from for a long time, he was well.

George met some friends in Barnsley. Benjamin James Batty, who was a Clerk, and also from Worsbrough Bridge, met George at about 8pm. Two other men, Joseph Fowkes and Charles Leeson joined them in the Market Place and they all went to the Wire Trellis Inn, where they met a fifth man John Fearn. They stayed there for about an hour, having a glass of beer apiece and went on to the Prince of Wales Beerhouse. At this pub they had something to eat and a couple more beers, leaving at 10.45pm. A third Beerhouse was attended, and the group had some more beer and left after 45 minutes. They next went to a friend’s house and George fell asleep for around ¾ of an hour. They loitered for 1 ½ hours at the friend’s house before beginning the walk home.

Benjamin later reported that George “had drunk more beer” than the others, “appeared to be in good health and spirits” and “was rather fresh and unsteady at first” and he had to hold his arm as they walked. Two of the men left the group and George walked on between Benjamin Batty and John Fearn. John left them by the Furnace Yard and Benjamin left George about 100 yards from the Mill house.

George returned home about 2.30am on Monday morning. His parents were woken by him arriving and his father protested about the lateness. George said he “would not be found fault with”, being depressed and a little drunk, he pulled out a six-barrelled revolver he carried while out late at night and fired at his own head. The first shot only grazed him, the second penetrated his skull.

George had been sitting on the stairs near the kitchen fire when the pistol discharged. His mother pulled him to the floor to prevent him falling and went for help to their nearest neighbour. Thomas Parrett of the Red Lion Inn returned with her, but they found that George had not moved. He was laid on his back on the hearth, with his father sitting close by. On the floor next to George was his revolver, Thomas picked it up and examined it. He also examined George’s head and found a mark from the right side at the back, 3 or 4 inches long in the direction of his forehead. The hair was grazed off. There was also a small hole on the right side of the back of his head. Blood and brains were coming out.

Dr Sadler of Barnsley was sent for and arrived soon afterwards. The doctor’s skill could do nothing to save him. George lingered for about 4 hours, dying at ½ past 7 on the morning of Monday the 3rd of October.

The coroner, Mr Thomas Taylor arrived the next day and held an inquest, at the Red Lion Inn, which was just a few hundred yards from the mill.

When George’s mother gave her evidence, she said during the last fortnight he had often said “he wished he was out of the way” and he’d said he was “disappointed in love and feared he was despised by the lady.”

Thomas Parrett who had examined the revolver, gave evidence that he found that 3 barrels were empty, the other 3 loaded. The 3 that were loaded had a charge of gunpowder and a leaden bullet. Thomas said that George sometimes came into the Red Lion Inn, and he had heard him say that he carried a revolver while out at night.

From the information the witnesses gave the jury returned a verdict that the deceased committed suicide in a state of temporary insanity.

He was buried in the graveyard across from St. Mary’s Church, in Worsbrough Village.

From everything I have learnt about this story I have two unanswered questions.

Firstly, who was the lady who broke George’s heart?

And second, there were only 2 bullets discharged in the kitchen that night, but a third bullet was missing from the revolver when it was examined. When and at whom did George shoot that third bullet?

Breathing Problems – The hidden killer

Working in factories, mines and mills in the 19th and early 20th century often came with a hidden killer. In textile factories the fibres of cotton or wool could get into the air. Mines had coal dust and in corn mills the flour particles would settle on every surface. All these fine dust particles would be breathed in by the workers and over the years this would unknowingly damage their lungs and lead to an assortment of breathing related diseases and afflictions. Worsbrough Millers were not immune, as can be seen in the following stories.

George Hanley was born in South Kirkby in 1818. His father was a farmer, and a windmill stood within the boundary of the farmland. George became an apprentice miller at around 12 years old and learned his trade in the windmill. Between 1846 and 1849 George moved his family to Wood Hall Mill in Darfield. This was a water powered corn mill and a step up from the windmill. By 1852 George had moved his family to Worsbrough Water and Steam Powered Mill, another step up.

In the census for 1861 the family are still at Worsbrough Mill. Thomas Hanley, George’s eldest son, had now joined his father working as a miller, probably an apprentice learning the trade.

1861 Census – Worsbrough Mill

George Hanley Head 42 Corn Miller

Mary Hanley Wife 40

Thomas Hanley Son 16 Corn Miller

John Hanley Son 14 Scholar

William Hanley Son 11 Scholar

Lucy Hanley Daughter 8 Scholar

But by the next year the family had left and were then to be found at Cheese Bottom in Thurgoland. George Hanley died there in August 1862, from Tubercular Disease.

Tubercular disease or Tuberculosis, also called TB, is a serious illness that mainly affects the lungs. TB can be spread by coughs and sneezes, projecting tiny droplets with the germs into the air. George Hanley had been milling since he became an apprentice, at around 12 years old. So, for 30 years of his life, he worked in a floury environment. Breathing the flour dust in the air, combined with the moisture inside the lungs, produces a doughy substance, making it hard to breathe. With weakened lungs George had unluckily been exposed to TB. He may have suffered for a long while, before finally passing away.

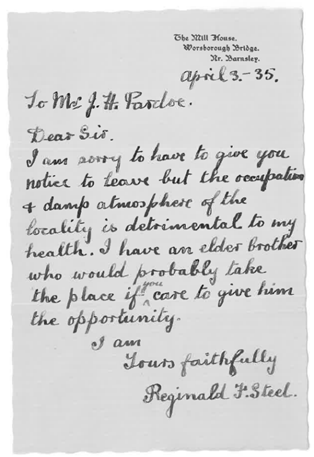

Reginald Steel

Another miller left the business due to breathing issues, he was Reg Steel.

Reginald Frank Steel was born in 1896 at Broomhead Mill, Bradfield. He was the 13th child out of 14 born to George and Elizabeth Steel. He grew up and learnt the trade from his father. When the First World War broke out Reg joined the army and was transferred to the Machine Gun Core in December 1916. Sometime during the war Reg was injured in a gas attack, leaving his ears damaged. After his discharge from the army in March 1920, he went home to Broomhead Mill. Because of the injuries to his ears, he often wore a balaclava while milling.

In 1923 the family moved to Worsbrough Mill. We know George and Elizabeth moved with adult children Herbert, Alfred, Reginald and Winifred. Bert and Alfred ran a threshing machine business, while Reg became the Miller.

Reg Steel ran the Mill from 1923 to 1936. When he took over, the mill and machinery were very old. From Reg’s account books we see he was making Oats and Bran, possibly as animal feed for local farms (see our previous blog for more)

By 1935 Reg was having some difficulties, he wrote a letter to the agent Mr Pardoe, informing him that he was giving notice that he intended to quit the house and mill in April 1936. He stated that ‘the occupation and damp atmosphere of the locality is detrimental to my health’.

Reg Steel had married in 1932 to Mary N. Furness. When they left the Mill in 1936, Reg was only 40 years old, but the occupation had taken its toll. They moved to a farm in Lincolnshire, the outdoor life must have improved his health, he lived to 78 years old.

I had assisted in the milling at Worsbrough Mill for around 13 years. We, in modern times know the dangers of flour dust and have protective masks. But even I started to withdraw from most of the dusty work about 7 years ago, as I had noticed that I had a persistent cough and was constantly clearing my throat. Luckily for me leaving the dusty environment has halted my symptoms.

Operations – Pain, infection and blood loss

While I was looking for another miller’s gravestone in the grounds around St. Mary’s Churchyard, in Worsbrough Village, I came across the stone of a man, and it states that he died at Sheffield Infirmary through an operation. It was a strange thing to write on a gravestone.

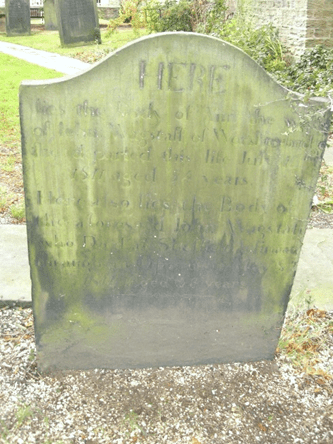

Photo and Transcription of the gravestone at St. Mary’s Church, Worsbrough Village.

Here lies the Body of Ann the Wife

Of John Wagstaff of Worsbro-bridge

Who departed this life July 16th 1811 aged 54 years

Here also lies the Body of

The aforesaid John Wagstaff

Who Died at Sheffield Infirmary Through an Operation

May 8th 1814 Aged 58 years

I had come across this man before, he was John Wagstaff, the assistant Miller at Worsbrough Mill. He was already a miller when he was first recorded in the local parish records in 1778 and continued to mill until he died in 1814. He had milled for at least 36 years and was 58 years old.

John’s wife Ann had died 3 years earlier. They had 13 children together and the youngest child John (junior) worked with his father as a miller’s apprentice. In January 1814 John and his son were witnesses in a trial of theft from the mill. A farmer called Thomas Wood was found guilty.

But within four months something had happened, which led John to need an operation. Was it an ongoing illness or the result of an accident in the Mill? We will never know.

Early 19th century surgery was hazardous and painful. There was a lack of anaesthetics and antiseptics. Operations were done quickly to reduce the suffering of the patient. The three key issues were pain, infection and blood loss, these led to patients suffering complications like shock.

Other medical practices doctors relied on to treat symptoms included bloodletting, blistering, and high doses of mineral poisons. This led to high death rates in patients.

For John Wagstaff to consent to having an operation at that time, what he suffered from must have been a risk to his life.

To be continued…..

While researching ‘Trouble at T’Mill’, I found more stories than I thought was possible, so I will end part 1 here, but I hope you have enjoyed these stories and will look out for part 2, which has Fire and Explosions and covers the changing landscape around the mill.

Have you read our other #WorsbroughMill400 blogs?