Continuing our year long celebration of #WorsbroughMill400 which has been made possible through funding from National Lottery Heritage Fund and support by Barnsley Museums & Heritage Trust Catherine Roebuck (Visitor Services Assistant) has been delving into the history of the 400 year old mill.

When I started working at Worsbrough Mill in 2006, local people visiting told me that they knew the place as ‘Watson’s Mill’ and two artefacts inside the buildings also made me want to find out more about the family and their time living and working at the mill. The first artefact was a fender, which is still in situ in the mill fireplace, it has a date of 1865 and the name ‘J Watson’ on it. The second item was a flat piece of metal with the words ‘J. Watson Worsbro Mill’, which would have been used to stencil those words onto flour sacks leaving the mill.

While researching I found the family milling with steam power, at the height of the industrial revolution, but also a family living through fire and tragedy and eventually to a declining business as the modern world passed them by.

The Watson Family moved to Worsbrough Mill in July 1862, and began the longest tenancy, ending in January 1923.

The family consisted of John Watson (senior), his wife Mary and their 6 children. By the time they moved to Worsbrough only George Thomas, aged 26 years and John (junior), aged 18 years, were still living at home. Both sons had been trained as millers and worked for their father.

The Early Years

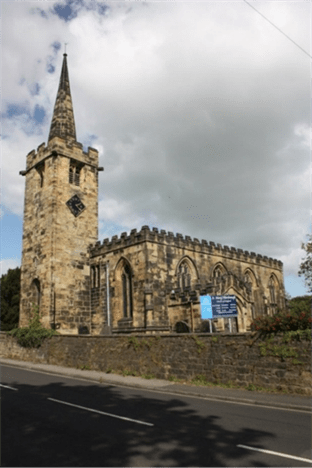

John Watson (senior) was baptised in August 1805 at St. Mary’s Church, in Worsbrough Village. His father Benjamin was a husbandman and looked after animals on a small area of land. He grew up in the Worsbrough area and started work in the Milling trade. John would have become an apprentice miller and trained for around seven years. He was living in the Silkstone area in 1829, there was a watermill in the area, and he could have worked there. He married at All Saints Church, Silkstone on 21st September that year, to Mary Wilby and their first child Ann, was born in Monk Bretton in 1830.

Burton Bridge Mill in Monk Bretton was up for rent around 1830 and John Watson went into partnership with George Jackson. The Steam Mill was near the Barnsley Branch Canal, Aire and Calder Navigation. Barnsley and Monk Bretton’s population grew fast during this period. Coal mines opened, the iron industries boomed, the canals carried cargos to and from the town. There was now plenty of coal in the area, it made sense to work one of the new steam powered mills. In the years that followed John and Mary had 5 more children: –

Sarah Selina born 1832

Mary born 1834

George Thomas born 1836

Benjamin born 1838

John (junior) born 1844

While the children were young John employed several assistant millers, but when the boys became old enough, they became apprentices under his instruction.

Just as things were going well, disaster struck. On 26th February 1842 the mill occupied by ‘Jackson & Watson’ at Burton Bridge was destroyed by fire. But by 1851 the mill was again a thriving business. Jackson and Watson also farmed 23 acres of land and employed 7 labourers: –

Richard Poppleton aged 21years Corn Miller

George Thickett aged 38 years Miller’s Carter

Joseph Thickett aged 16 years Farm Boy

Samuel Thickett aged 14 years Farm Boy

Robert Chamberlain aged 34 years Corn Miller

George Thomas Watson aged 15 years Miller (son & Apprentice)

Plus, an Agricultural Labourer

The two men grew their own wheat and in August 1852 one of their fields was used in a trial of a Reaping Machine. A large audience of trades people, farmers and labourers came to witness the operation of a ‘Hussey’s American Reaping Machine’. The reaping machine was horse drawn and used during the harvest to cut and gather ripened grain crops. The trial wasn’t wholly successful, the day was wet, and this hindered the machine and the man following could not clear the platform quickly enough, but all the spectators could see the potential.

In August 1857 John had problems with one of his employees. He had been employing members of the Thickett family for around 10 years, when Benjamin Thickett was caught stealing a pair of horse blinders and a pair of frames which were John’s property. Ben pled guilty and was sentenced to 1 month imprisonment. But he kept his job and was still employed as a mill servant in the 1861 census.

In the 1861 census it is listed as ‘Burton Bridge Steam Flour Mill’, son John (junior) had now joined his father and brother working the mill, and partner George’s nephew, Joshua Jackson and Joshua’s son William had joined them as Millers.

Idea for image – Map with steam mill on Barnsley canal

Within a few months of the census George Jackson and John Watson dissolved their partnership by mutual consent. In July 1861, this end was published in the Barnsley Chronicle and John Watson moved out of the mill to a corner of Monk Bretton called Belmont. They lived there for around a year before the mill at Worsbrough came up for rent. John may have jumped at the opportunity of running his own mill with his sons, he knew the area from his childhood and was returning home.

The move to Worsbrough Steam Flour Mill

An advert went in the Barnsley Chronicle on Saturday 12th July 1862, for the house in Monk Bretton where the family had lived, ‘To Be Let’ to new tenants. The Watsons had moved and taken up residence at Worsbrough Steam Flour Mill and Farm.

A piece of information on the 1861 census states that John Watson (senior) was blind. When they arrived at the mill son George, aged 26 years, managed the business for his aged and blind father. Son John (junior), aged 18 years, left home around this time and was thought to be training for a different career.

Tragedy struck in October 1864. George Thomas Watson, although working well for his father, had become disappointed in love, feared he was despised by the lady and had become quite depressed. He went into Barnsley one Sunday afternoon and met some friends. After visiting several beer houses, the group walked back to Worsbrough. He walked the last 100 yards on his own, arriving home at ½ past 2 in the morning. His parents were woken by him arriving home and his father John protested about the lateness. George being depressed and drunk pulled out a six-barrelled revolver he carried while out late at night and fired at his head. The first shot only grazed his head, the second penetrated his skull. George Thomas Watson died at ½ past 7 on the morning of the 3rd of October, age 28 years and was buried in the graveyard across from St. Mary’s Church, in Worsbrough Village.

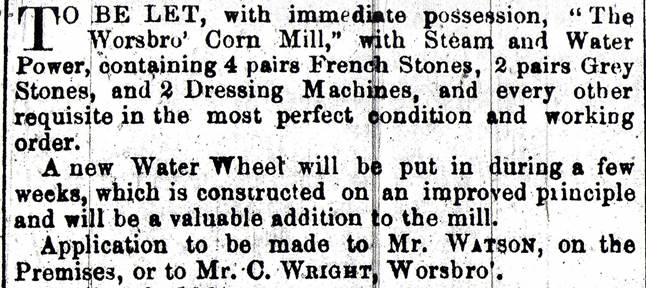

After this sad incident, John (senior) decided to leave the mill and it was advertised in the Barnsley Chronicle, in October just days after the death of his son.

John and his wife Mary did not leave the mill. John (junior) returned to help his father with the business and stayed, marrying a local farmer’s daughter, Sarah Ann Saville in 1867.

Sadly John Watson (senior) died in March 1870 and Mary Watson died in May 1875. Both were buried with their son George, in St. Mary’s Churchyard.

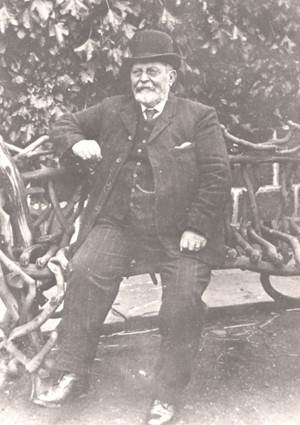

John (junior) was still a young man and with his wife Sarah they now had an established milling business, which they continued to run for the next 5 decades. At the start it was a thriving business and John hired several millers, carters and farm labourers, over the years to help out. But this wouldn’t last.

During John’s time at the mill, he employed several men.

One was Thomas Heppenstall. Thomas worked at the mill for 11 years and lived at Red Lion Cottages, which is just across the road near the Red Lion Inn. He was married to Martha and had 7 children, aged 15 years down to 3 months. In 1881 Thomas had a fatal accident in the mill and died within an hour. He was buried at St. Mary’s Church on 27th April 1881, aged 39 years.

George Coope was also employed at the mill, as a Waggoner. He was lodging with John Watson at the time of the 1881 census and witnessed Thomas’ accident that same year. At some point after this he moved to Wakefield to live with his brother Thomas Coope, a police constable. He married Louisa Jane Fletcher at All Saints Church, Wakefield. Louisa’s father, James was a Corn Miller. By the 1891 census George and Louisa were living at 23 George Street, Worsbrough and George was back working as Watson’s ‘Drayman’, which he continued to do until his death.

John (Jack) Thomas Nicholson was employed by John Watson as Miller. We know Nicholson was at the Mill in 1894, as he married Mary Ellen Wood at St. Mary’s Church, and their children Edith, Florence and Alice were baptised at St. Thomas Church, Worsbrough in the following years. At both his marriage and the baptisms of his children he was listed as Miller, living at Worsbrough Bridge. He was still living at Park Road, Worsbrough, as Corn Miller, in the Census 1901.

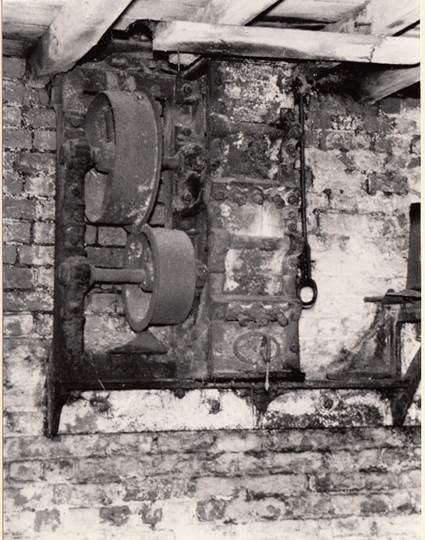

The Decline of Water Mills

Water powered mills have been around for at least 2000 years. But by the mid-19th century new sources of power were driving traditional mills out of business. First steam power, then oil, diesel and later electricity, all of which were much more efficient and not dependent on water. Also new technology, the more sophisticated roller milling machinery arrived, which used small rollers to crush the grain instead of large millstones.

In place of old watermills, vast factory like developments sprang up, built alongside ports, navigable rivers and canals. They could obtain grain from overseas and produce flour in quantities never seen before.

Traditional mills tried to keep up. The roller mill machinery was smaller and more efficient, and the manufacturers of the new machinery advised older mills on how they could adapt. They could attach the new roller mills to be driven using waterpower. Mills that also had an engine of some kind could couple it up to the new machinery. This provided the old mills with a chance of keeping up with the larger Roller Mills, for a time.

Only the enterprising miller, could adapt to this new technology, as it was very different. Instead of wooden gears and shafts, operated with skills passed down through generations, millers now faced complex modern machinery. Many traditional millers were driven out of business, the mills were left derelict or converted to some other use.

Although Worsbrough Mill already had steam power when the Watsons took over, they never changed to the new roller mills, so gradually business declined. John Watson continued at the mill until 1923 when he died and was buried at St. Mary Church, on 29th January 1923, aged 78 years

John and Sarah Ann Watson did not have any children and therefore Sarah would have given up the tenancy after John died. Within a couple of weeks, the ‘Valuation of Probate’ of John Watson’s estate took place. Household furniture, Mill fixtures, fittings and stock, implements and tools, also the value of Tenant right in grass land, 50 hens and an old mare were all for sale.

Amongst the household items up for sale were 7 glass cases of stuffed birds. These surprising items were the result of the Victorians’ fascination with nature. After Charles Darwin wrote ‘Origin of Species’ and explorers started to travel the world bringing back extraordinary animals, people became interested in the world’s creatures and wanted to bring nature into their homes. Glass cases of exotic birds became the fashion. A more personal item valued was John’s silver watch and a Bean Kibbler used for processing bean and peas to make animal feed, was also valued, but this must have been sold to the next Miller, as it can still be seen in the mill today.

John Watson’s estate was valued at £172 – 8 shillings. Sarah Ann Watson died in 1926 and was buried with her husband.

The Watson’s came into milling at the height of the industry, and then witnessed the small mills gradual decline as larger mills took over. But the legacy they left behind was to have the longest tenancy in the mill’s history, spanning 60 of the buildings 400 years.