The first record of a mill at Worsbrough was in the Domesday book of 1086, although the exact location of the mill along the River Dove is unknown. The oldest part of the mill standing today dates from about 1625 and forms the two storey stone building known as the Old Mill, which houses the waterwheel. This means that it’s the mills 400th anniversary this year.

With support from The National Lottery Heritage Fund and Barnsley Museums and Heritage Trust we are celebrating this milestone (or should we say millstone?!) year in various ways throughout 2025 and as part of these #WorsbroughMill400 celebrations we are delving into the history of the mill. In this article Catherine Roebuck (Visitor Services Assistant) explores the life of a former mill inhabitant, Ann Shaw.

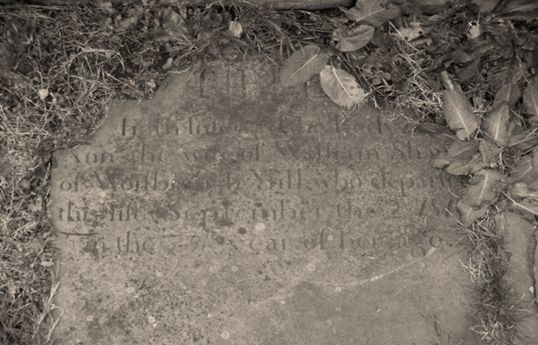

There is a date on the chimney breast inside the Old Flour Mill at Worsbrough, 2 Sep 1819. For a long time this date had no explanation, until a grave was discovered in Saint Mary’s Church Yard, Worsbrough Village. The grave was that of Ann Shaw.

“Here Lieth Interred the Body of Ann the wife of William Shaw Of Worsbrough Mill who departed This life September the 2nd 1819 In the 75th year of her age”

Finding this stone led to the discovery of a lady who not only survived to a great age for someone living in the early part of the 19th century, but she ran a milling business and died a wealthy woman within her community.

Little is known about Ann’s early life. She was born in Heddon-on-the-Wall, Northumberland in 1746. Baptised Ann Fenwick, she had an older sister Mary, who never married and an older brother Stephenson Fenwick, who went on to have 6 children. At some point she married and became Ann Storey. Ann was later widowed and moved to Worsbrough, where in 1799, at 53 years old, she married again this time to William Shaw. He was a bachelor of around 46 years and the Miller of Worsbrough. William Shaw was first recorded as the Miller of Worsbrough in 1782, when he paid his Poor Rate Assessment.

This photo shows the oldest part of the mill that Ann would have known. She lived in the mill house on the terrace above the mill.

During Ann’s time at the mill several interesting events happened. The first being the coming of the canal.

The Canal Age

The construction of the reservoir behind the Mill, which was built to supply water for the Worsbrough Branch of the Dearne and Dove canal system, had already started when Ann moved into the mill cottage. She witnessed the terrible disruption to daily life. Dozens of wagons constantly coming and going, bringing stone for the dam wall and removing earth. Hundreds of navvies and their families moved into the area, all needing to buy flour. This meant more work for the mill, but the water supply would be constantly interrupted by the building work. Ann and William would also have witnessed several of their fields disappearing under the rising waters as the valley flooded. The Canal opened in 1804.

This brought new opportunities to Shaw’s Mill. The possibility of bringing wheat up the canal and taking flour further away to new markets.

William worked as the Miller of Worsbrough Mill for at least 24 years. Ann helped her husband run the Mill, from their marriage in 1799, until he died in March 1806, aged 53 years. He was buried in St. Mary’s Churchyard, Worsbrough.

Ann then took over as Manager. She employed several Millers over the next few years. Firstly John Wagstaff (senior), he had milled with her husband, and he continued until 1814. John Wagstaff (junior) started as an apprentice under his father and William Smith, Ann’s nephew, was also employed as Miller for a time.

Toll Milling to Merchant Milling

When William Shaw took over running the Mill around 1782 it will probably have been run as a Toll Mill. Customers would have brought small amounts of grain to the mill for grinding and instead of money changing hands the Miller would have kept 1/16th of the customers milled meal.

During the last decade of the 18th century Corn Mills underwent considerable change, owing to social and economic pressures. In 1796 Parliament passed the Act for Better Regulation of Mills, which regulated the miller’s toll and encouraged a change to a monetary system instead.

The population of Worsbrough started to increase with the arrival of the canal. Ironworks, coal mines, glassworks, boatyards, gunpowder mills, and several other industries sprang up along the valley. With this influx of people to the area, Shaw’s Mill would have adapted quickly becoming a Merchant Mill. Buying in grain from local farms and selling direct to the new growing population and later to local bakeries. Ann and William Shaw became quite wealthy during this period.

Theft of Meal from Shaw’s Mill

In 1814 there was a trial for theft at the Quarter Session in Doncaster on 19th January. Amongst the witnesses were John Wagstaff (senior) and John Wagstaff (junior).

A man named Thomas Wood was put on trial for stealing forty pounds weight of Barley meal valued at ten pence, the goods were stolen from Ann Shaw’s Mill, on the 1st May 1813.

John Wagstaff (senior) was the head Miller, with apprentice son John Wagstaff (junior) aiding him in his work. John was about 14 years old at the time.

Thomas Wood was a farmer in Worsbrough. He went to the Mill with his servant lad, George Conway. Wood ordered George to go with him to the Mill to get a ‘met of hinder ends’ ground for his pig (hinder ends – the light stuff blown off when threshing). On the way Wood said to George “I’ll take old John Wagstaff into the top chamber and keep him cock-a-spell whilst thou must get a little as we shall not have enough to serve till winnowing again”. John (senior) was not around so Wood took the miller’s son, John (junior) up to the hopper to put his hinder ends in. Wood returned back downstairs and said to George “old John Wagstaff is not in, we have a nice chance”. In the ark of the mill was a quantity of barley meal which was put together at one end, leaving the other to receive the meal grinding from the hinder ends. John (junior) was then below, but on the ringing of the bell, indicating that the hopper was nearly empty, he ran upstairs to stop the mill. Wood opened his sack and told George “Put some of the barley meal in”. Wood then filled his own meal, and after carrying the sack on his back a short distance gave it to George to carry, saying “Damn me George, we’ve got a rare lump this time. It’ll serve the pig a good bit”. This was reported in the Doncaster, Nottingham and Lincoln Gazette in January 1814.

Thomas Wood confessed to the crime and was ordered to be confined till the rising of the court.

Ann’s later years

After her husband died Ann was alone in the mill house, but her elder sister Mary came to live with her. Ann Jobling, the sister’s great niece also came to live at Worsbrough Mill sometime between 1811 and 1819.

Ann Jobling had been working in London and gave birth to an illegitimate child, William in 1811. She needed somewhere to live. Ann Shaw was getting old, together with her ageing sister Mary, they would have appreciated the help. Ann Jobling and her son lived at the Mill until her Great Aunts died.

The ageing Ann Shaw started to make her Will in 1818, which she amended 3 times, the last amendment was on the 10th May 1819, 4 months before her death. The Mill was now a Merchant Mill, and this would account for the large amount of money Ann left in her Will.

Ann died on 2nd September 1819, aged 74 years. Her gravestone can be found in the path, at the tower end of Saint Mary’s Church, in Worsbrough Village.

Ann was a wealthy woman when she died. Leaving £400 in Stocks and Shares, £200 cash and many silver items to relatives. She also left £20 for the Village Sunday School.

Ann Shaw’s Circle of Influential Friends, Associates & Family

The Biram’s of Wentworth

Mary Biram was a friend of Ann Shaw and attended Ann’s marriage in 1799 at St. Mary’s Church. Mary was married to Joshua Biram who worked for the Earl Fitzwilliam of Wentworth Woodhouse as his Steward. This made him one of the most influential men in the community, with the roles of ‘Superintendent of the Wentworth Estate’ and ‘Superintendent of the Collieries’. He was the Earl’s personal representative and was responsible for the accounting, mining engineering, labour management, sales and marketing on the Wentworth Estate.

Mary and Joshua had several children baptised at Wentworth Church including son Benjamin in 1803, who follow in his father’s footsteps and daughter Ann Biram baptised in 1808.

Eleven year old Ann Biram, the daughter of her friend Mary, must have been important to Ann Shaw as she was left 2 silver Tablespoons in her Will.

Edmunds Family of Worsbrough Hall

Worsbrough Hall consists of a central house with two wings, in the Elizabethan style of architecture. Since the early part of the 17th century, it has been the residence of the family of Edmunds. It continued to be their residence until the death of Francis Offley Edmunds in 1831.

William and Ann Shaw rented Worsbrough Mill from Francis Edmunds. They knew Francis, his wife Hannah Maria and their 3 children, Maria Elizabeth, Urith Amelia & Francis Offley Edmunds.

When Ann Shaw died, she left Miss Urith Amelia Edmunds & Francis Offley Edmunds Esquire of Worsbrough the sum of £20 in her Will, for the Encouragement of the Sunday school.

John Birks, Gentleman of Hemingfield

John Birks was baptised in Darfield in 1771 and married Elizabeth Swift there in 1803. He lived in nearby Hemingfield, on a large farm of 278 acres, which employing 10 men and boys. He and two of his sons worked mainly as Attorney’s in the local area. Ann Shaw must have known him quite well as she made him one of the executors of her Will and left him £5 for his own use.

Martha Spivey, wife of Joseph Spivey

Martha Shaw born about 1782, married Joseph Spivey in 1803, at St. Mary’s Church, Worsbrough. Martha was a relative of Ann’s husband William Shaw. Ann left her several items in her Will:

Canop bed stead hanging

Feather bed bolster 2 Pillows

3 Blankets 1 pair of sheets

1 tablecloth 2 silver dessert spoons

5 silver teaspoons 1 plated tankard

Great Niece – Ann Joblin

Ann Jobling came to live at Worsbrough Mill sometime between 1811 and 1819.

Two months after her Great Aunt died, she married a farmer John Saville at Darfield Parish Church. Ann would have been a good catch having recently inherited £200, from Ann Shaw.

She also inherited all Ann Shaw’s wearing apparel, 1 white bed quilt, China Tea Set, 2 silver tablespoons, 2 salt spoons and 1 large Bible by John Brown.

Ann and John Saville moved back in Worsbrough Mill from 1832 to 1837, with her son William Jobling who was now working in the milling trade. It may have been during this period that the date of Ann’s death was inscribed on the lintel of the fireplace, inside the mill.

Brother – Stephenson Fenwick

Stephenson Fenwick was baptised in 1743, married Mary and they had 6 children. The family were settled in Winlaton, near Ryton, Northumberland.

Ann Shaw had no children so left her money to 14 nephews and nieces. Three of Stephenson’s daughters, Ann, Elizabeth and Hannah inherited 1/14th each of all the Residue (everything left) of the general Trust Monies and after the death of Ann’s sister-in-law Mary Smith, to sell out the £400 Stocks or Funds and they would get 1/14th share of that as well. It maybe that Stephenson’s other children died young, as they didn’t receive a share.

Ann Shaw died a wealth woman on 2nd September 1819 having spent 20 years running Worsbrough Flour Mill. The Mill changed from Toll milling to Merchant milling, the canal came, and many industries sprang up along the valley. The population increased as the job market grew, and the mill was busier than ever. The total value of her estate would have been heading up to £1000, which was substantial for that period.

Ann Shaw Remembered

The ‘mill song’ bench and poem pays tribute to Ann, the words from the poem written by Eloise Unerman appear on the bench, you can also listen to Eloise reading her poem

This article was first shared to coincide with International Women’s Day 2025, see and hear from other Barnsley women, past and present on our website. The Millennium of Milling project has been funded by The National Lottery Heritage Fund and Barnsley Museums and Heritage Trust