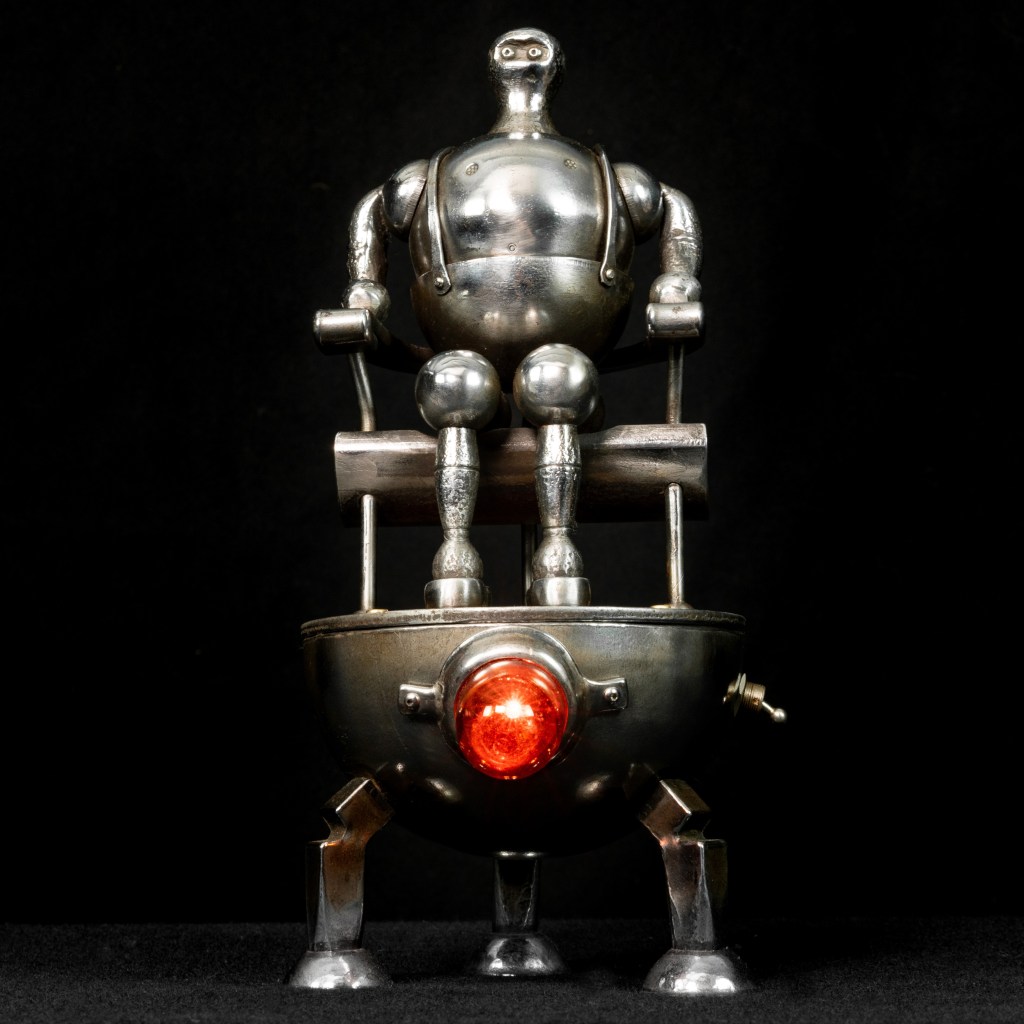

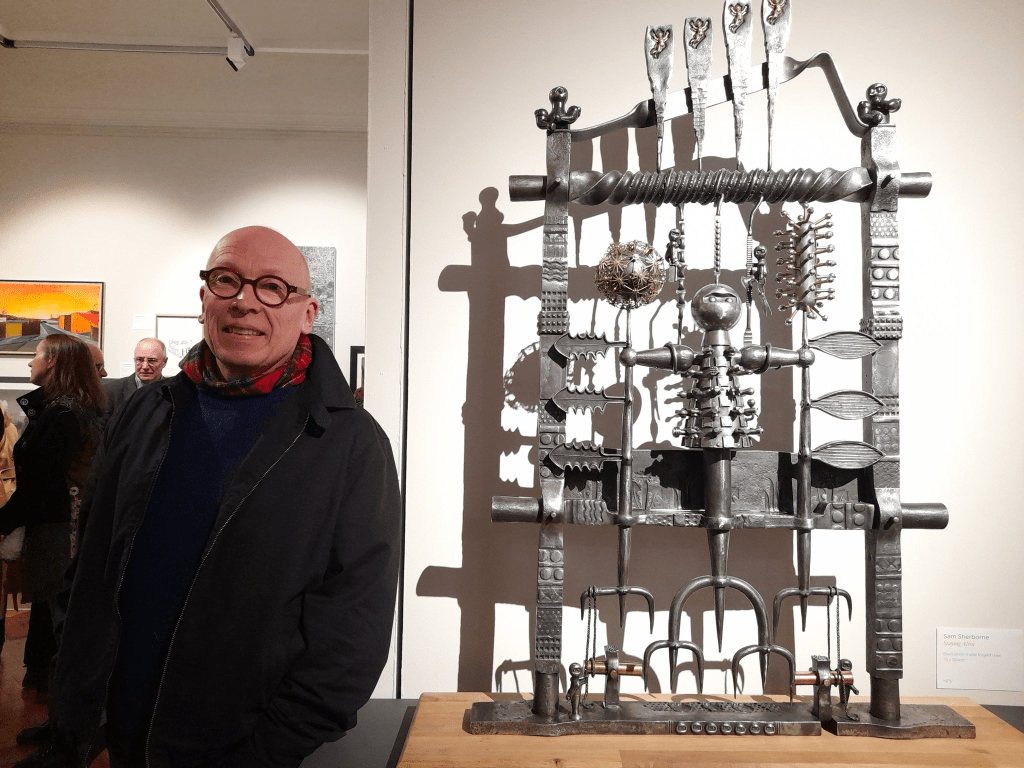

Sam Sherborne is an artist blacksmith and the winner of the prestigious South Yorkshire wide open art competition, The Cooper Prize 2023. One of the prizes for winning the competition is a solo exhibition at The Cooper Gallery. Visitors have the opportunity to see “Softening The Blow’ an exhibition by Sam which features 20 of his sculptures which are on display in the Sadler Room until 29 March 2025. Ahead of the exhibition opening, Sheauran Tan (Freelance Curator) caught up with Sam to talk about his life, work and inspirations.

Firstly, can you share with us the story of your artistic blacksmith journey?

Yes, well, this question seems quite a big question, and it’s difficult to know where you want to zoom into, but generally speaking, it’s been one of moving from acquiring skill and using the skill I have at the time, initially to make money, so that I can pay the rent for the workshop, buy the materials in and then at the end of the story, currently, well, hopefully this isn’t quite the end, I can please myself more.

I’m making art, so it’s from decorative art that I could make money from to fine art. Fine art sounds a misnomer, in some ways, it sounds pretentious, but all that fine art means is art that isn’t decorative, and its only function is as an art object. So it’s a journey from decorative art to fine art, from the commercial to the uncommercial.

There’s other themes in that journey of evolutions. So I’m constantly trying to find new ways to get flow, the psychological state of flow, which is quite addictive and very enjoyable. And it’s what makes you capable or willing to do masses of hours of work, which would have, a lot of people would find very boring if there was no flow.

They’d rather do something else. You know, sit on a rock in the Peak district and look at the sunshine. You know, they wouldn’t be in a little dark cellar beavering away if they weren’t experiencing flow. So the journey is reinvention. So more recently, I’ve reinvented myself as a memorial maker.

So that gets my work out of the workshop, not in the gallery. It’s in the urban landscape with Sheffield. I’m about to evolve into something else at the moment, I think, because I’ve got to stay interested and keep the flow coming. The other aspects of the journey are acquisition of more skill.

You know, it’s a constant journey. I’m always meeting new people who can inform my technical ability. It’s been great meeting people along the journey. It’s been great working in different places. The journey, I started off in my bedroom, then I built a shed (a scrap yard)

Then I managed to wheedle my way into a museum forge which was very well equipped. Then I buried myself in the countryside, which I didn’t like at all because I was too isolated. And then the current part of the story is Sheffield, which is just about perfect, really.

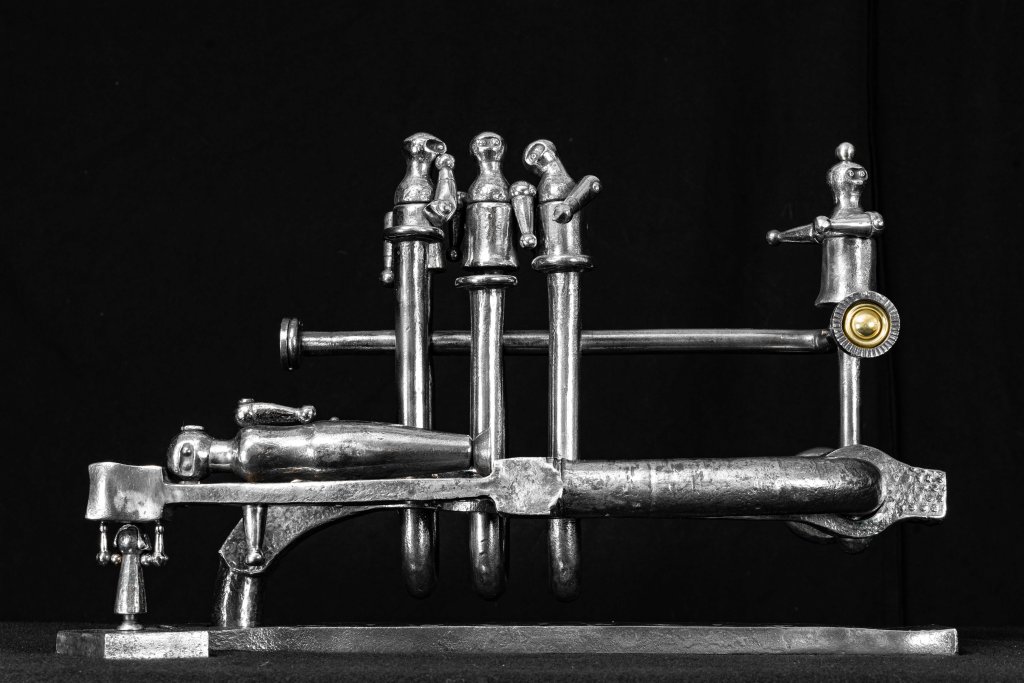

So the journey is looking for flow, evolving the skill, finding a new place to work and try, you know, trying to make beautiful things, beautiful, meaningful things. The things have become more meaningful because, I mean, at the end of the day, a piece of furniture or candlestick is only meaningful up to a point.

Whereas if you’re, you know, with a piece of sculpture, you can,imbue it, hopefully with more meaning you know it’s the personal expression, hopefully a universal message and a personal message. Whereas initially a candlestick or a piece of furniture is quite, you know, it’s just a design.

So I basically ended up near where I wanted to be when I was 25, but couldn’t because I had to earn some money. So that’s the journey of the artistic blacksmithing.

So when would you say you officially, as such, start at your journey? in this field. Have you always been working in this field?

No. So I left university and I got a job in a gallery of Southeast Asian Antiquities. I was the sort of flunky. I didn’t really do anything very clever. I just, I didn’t really have anything to do at all. So I could really look at the statues in a great detail. So I might have a 9th century nepalese Buddha just sitting next to my typewriter on my desk, where it should be really in a bulletproof glass case.

And I’d be carrying them round. I’ll be taking them from one display case to the next. And I could really absorb what they had in them. I mean, they’re absolutely fabulous objects. I’ve not experienced anything similar since. I mean, if something’s behind a glass case or a long way away on a shrine, in a temple, you can’t really interact with it so well.

But these things, whether they should have been in this gallery or not, I don’t know, but I was, I had direct exposure to them. So anyway, I did that for two years. And after,a while, I didn’t think selling was really something for me. I wasn’t very good at selling.

I wasn’t especially interested in it. I decided I wanted to make art, not sell art. So then that’s the journey of acquiring skills. And I didn’t want to go to art school because art schools all about seems to be trying to direct your creative image or tell you what’s allowed as a valuable creative image.

I didn’t have any problem with that. I had kind of confidence that what I, what I wanted to do, it just didn’t have the medium to do it in because I didn’t have the technical skills. So,I went to the London College of Furniture and learned woodwork which seems why would I do that since I like the metal sculptures? You couldn’t learn bronze casting, you couldn’t learn blacksmithing in London in the eighties and so I was making furniture, and my furniture gradually became more and more metal and probably the critical moment was walking into a forge in this museum and cooberish steam museum, saying I wanted to make a component for my wooden table.

The blacksmith there just pointed at the machine and said, you make it. It’s, the machine’s there. I can’t be bothered. If you can be bothered, it’s there. And then basically, I wasn’t out of his workshop for the next five years. And I learned a lot from him.

And it’s a fabulously well equipped workshop, so it was a lot of luck, really. So, yeah, I can still remember the moment walking into the forge. I mean, it was a very old victorian, or early victorian forging. It had a zeppelin bomb on it in the first world war and it had a great story and a great atmosphere and, uh, it was a really good creative space to operate from.

So that, uh. Oh, yeah. And then probably a very important moment was having my first piece of hot metal out of the forge. You know, all orange and red, having been black and cold, and then just bending it round a former and it just flows. It’s like plastic, it’s like rubber.

It’s gone from this totally rigid intransigent thing, you know, doesn’t want to do anything you want it to do to. When it’s hot, it’ll comply, it’ll do any. It’s plastic. It’s what a friend of mine calls the wonderful plasticity of hot steel and you can do anything with it, obviously.

The frustrating thing is you can’t touch it with your fingers. So blacksmithing is about shaping the hot metal without getting your fingers burnt. So you have a whole range of tools to be able to do that, to do it safely and effectively. So that was, you know, that was the pivotal moment, walking to the forge.

It’s still there, the forge. I mean, I got the use of it by keeping it open at the weekend. So I had worked, volunteered Saturdays and Sundays and, that meant I could use it during the week. Now, if you want to use it, the rent is just, you know, I don’t know, it’s just a big figure that anyone who was setting out wouldn’t be able to afford it.

And the training I had as well was virtually free as well in the London College of Furniture. Now, it would be, you know, a lot of money, so I feel sorry for the youngsters today.

What does winning the The Cooper Prize mean to you?

When I’ve been doing the work, I haven’t expected any external validation but and also I read a quote by Picasso where he said that 70% of the artist’s life doesn’t involve an audience. So 70% of the gratification you can get from making art does.

You don’t need an audience for that. So I was kind of maxing out on that 70%. I wasn’t showing my work. I wasn’t putting, it on social media or anything like that but I was getting all the things that you can get without an audience but it comes to a point where you think, well, maybe I should see if I can get some of the 30% as well.

Maybe I can have the whole hundred percent, if I was really lucky. I mean, I felt pleasantly surprised, to be honest. Very pleasantly surprised. My wife actually cried when it happened, which she doesn’t. She’s not a big crier, to be honest.

So I figured out it must be good because she knows I do work pretty hard. And I have been beavering away for, you know, best part, nearly 40 years. So it was nice that somebody could see some value in my work, which, I felt, you know, it’s brilliant, really brilliant.

And there were some lovely people there and they said, oh, your work, it wasn’t difficult to award you this prize. You, you were the clear winner. It wasn’t touch and go that someone else was going to win it. The whole thing is, there’s a lot of luck with these things because whether your work talks to the judges or not involves luck, you know, because your work can be brilliant, but it does not talking the language that the judges are versed in.

I think on the day at the Cooper prize the language I was using the judges understood it. They’re amenable to them. I think one of them might have had Some experience with jewellery and staying alive is like a big piece of jewellery, like a 1.51 meteres piece of jewellery.

In some ways, it’s a little bit disarming because it’s quite addictive. It’s nice when that happens. You think, oh, I want that to happen again. But that sensation of wanting it to happen again is not going to make you make any good artwork.

In fact, it’s going to have quite the opposite effect. So you have to kind of blank it all out and get back to work and hopefully make the really good thing regardless of exhibitions and prizes and stuff like that. So it made me a bit confused as well.

Do you have any upcoming projects or exhibitions planned?

No but I have some new materials that I want to make sculptures with and hopefully I’ve got some intensive workshop time planned rather than exhibiting then, you know, where you’re driving around the country getting sculptures ready, painting plinths. I don’t want to be doing that.

So I’ve got some workshop time planned and I’ve got twelve bits of railway track, which are about two and a half feet long each. I think they’re off cuts from the rail, you know, the rail track company. And, um, and they’re really, really heavy. I mean, seriously heavy. I mean, basically one, I can pick it up, maybe not off the floor, I couldn’t pick it up, but I can pick it up if it’s on a table and walk a few feet with it.

But it is really, really heavy. So I want to make these twelve sculptures while I’m still strong enough, using this really heavy stuff. So it’s the sculptures that’s planned, that’s the next thing. it’s fabulous material and so, yeah, I’m quite excited about that. I’m just a bit scared of the weight. I probably need an assistant

So when did you start making sculptures? How did you move from making furniture to the current sculptures now?

Well, the first thing that looks anything like any of my sculptures was made for my daughter’s 18th birthday and it was, it just said her name, “Dora love dad” on it and it was a sculpture, really, and it. She’s 28, so ten years ago, really, that was the first thing.

It took a long time to make and now I look at it and I think, well, it’s not that brilliant. So I think I’ve come quite a long way in the last ten years. I mean, it’s partly allowing yourself to make something uncommercial. And that’s purely, satisfying your own need to make something.

And it can. It feels very risky allowing yourself to do that. So I got to a time where I thought I could allow myself to do it. So if you look at the dates of my sculptures, the early ones, I don’t go farther back than 2017, which is seven years.

So the first three years, I really didn’t make anything I was very pleased with. But in 2017, I started making stuff that I liked and then the friend made the film, which is the one I sent the gallery. So I didn’t edit that at all. That’s purely his image.

And I think he makes me look quite of an eccentric old weirdo, to be honest. But you know what? You know, maybethat’s true! He’s a very talented filmmaker, I let him do it. It’s definitely not an advert for me, not as far as I can see, anyway.

What’s his name?

Joe O’Connor. He was at school with my son and he’s a friend of mine as well. so I saw him the other day. He lives in Greece now, he’s a musician and a filmmaker in Greece. But he came to my son’s wedding. He came all the way from Greece just for that. So it’s difficult to see him unless you go to Greece. But I saw him recently.

He doesn’t know how talented he is so he doesn’t pursue it hard enough he’s had, you know, when you setting out creatively, you have lots of knockbacks and you’ve got to ride the knockbacks and keep getting back on the horse. And I think he had a few knockbacks and he’s just thought, I’ll do something bit more straightforward.

Is there anything else that makes you change the direction of your flow?

The flow is a psychological state you get when you’re working. It’s not a direction it’s you know, time becomes irrelevant. Time can go very quickly or very slowly, but you’re not focused on time. You feel very calm, you feel very focused.

You can do a lot of hard work without even realizing you’re doing very hard work. It’s only when you get to the end of the day and you realize you’re totally exhausted. I mean, what I did say was you have to reinvent a context where that flow keeps coming so you can access that frame of mind.

I like to run things past people. Yeah, certain people, not just any old person. Someone who, you know, if they say something’s really brilliant, you know what that means for them, you know, because you know their vocabulary, you know their constructs. And if they say, oh, that’s terrible, but they never normally say things are terrible, you know, it really is terrible.

But mostly I find it’s better not to take any notice of external opinions or make anything with any goal of pleasing some external person. External validation, I find that kind of waters things down. If you want to try and second guess what’s going to be good, you’ll end up making something less good.

You’ve just got to make the thing that you want to make and you can maybe bounce it off chosen individuals. But mainly it’s I don’t take much notice of anybody else or If I am taking notice of other people, the thing ends up being not so good because it’s almost designed by committee.

It’s like a vision. You have the vision, and then to make it the thing, it’s got to look exactly like that. And anything coming in externally, apart from that one message, can water it down and make, you know I can get confused and end up with a thing that I didn’t intend to make that has lost the original inspiration.

So I’ve done that by trial and error, you know, I mean, I did experiment with being on social media, and I found that was like a disaster for my work.

Have you ever experienced creative blocks? So, like, you just don’t feel like an off day?

Um, well, it’s not really off days. It’s more like off periods. And then so since I’ve been doing the sculptures, I pretty much don’t have off days because I’m quite fired up by them. So that’s the last ten years. But, I can have days where it’s not completely off, but it might not be as good as a really good day and that can be just because I’m tired. So it’s just been physically tired rather than blocked. When I first started making artwork, when I allowed myself to make artwork, there was a bit of a big block, because I was thinking, well, what am I going to make? You know, I’m not going to make someone’s gate anymore. I’m not going to make any railings.

I’m not going to do anything like that. I want going to make some artwork. It’s a bit like tuning into a FM radio, the old fashioned ones. If you’re in the middle of nowhere and you’re trying to get, I don’t know, Classic Fm or something, and it’s just a tiny little bandwidth, and you turn it.

And I’ve stolen this image from someone called Rick Rubin. But for me, it’s perfect. You tune into the radio and it’s very difficult. You get all the noise, the kind of squeals, the shrieks and the strange noise the radio makes, and then you’re on, you’ve got it. It’s transmitting clearly.

The music information is coming brilliantly, and it’s about keeping that, keeping yourself well tuned in. And that means looking after yourself, not getting too tired, not eating rubbish food, not doing plenty of exercise having rest when you need a rest to keep the. Keep the transmission coming.

But I think if the transmission is very strong anyway, you don’t lose it completely. It just might not be quite so broad. But when I first started making the artwork, or trying to make the artwork, then you could definitely say that was a block, because I was thinking, well, what am I going to make after about.

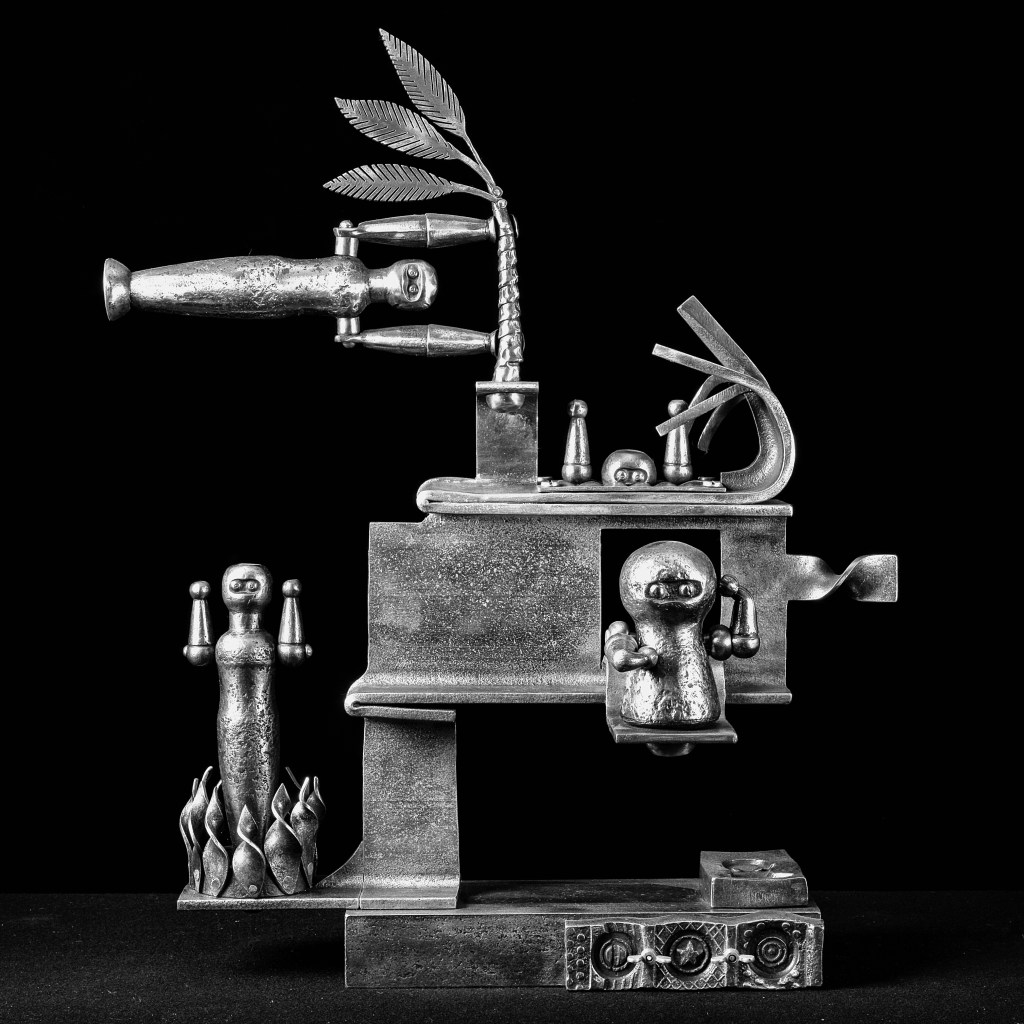

And I did experiment with abstract art I use abstraction a little bit in the artwork to set the mood of the sculpture, but it’s not the meaty part of the storytelling of the sculpture. I found abstract was too wooly asks. It’s too subject, you know, the viewer is asking too much of the viewer.

I mean, a lot of blacksmith art looks like swirly things. They make kind of swirly things. And because it doesn’t actually do anything, they call it art, but really it’s just a swirly thing that doesn’t really mean anything at all. So I didn’t want to be the man who makes the swirly things anymore, like most blacksmiths and so.

But the blacksmith I did like but I don’t think I’ve been influenced by him too much because his message is completely different to mine. As far as I can understand. His message is. Chelida is a Basque Spanish blacksmith going back a few decades now and beautiful abstract work.

What would you consider artwork that’s meaningful to you?

It lifts you from the moment you have a glimpse. So, one of my sculptures is called the glimpse. But a good piece of art can give you a glimpse of, or an overview of what you’re actually doing in your life. You know, rather than just rushing around, chasing bills, paying the rent, getting tired, firefighting, all kinds of things, suddenly you get a bird’s eye view, a massive panoramic view of what’s going on, who you are, what the whole point is of everything.

But it’s momentarily, it’s momentary. So just as you think you’ve got that knowledge, it’s gone. But at least you had it for a second so that’s what good art does. It gives you some perspective and unfortunately, it won’t last for very long, but it’s better than nothing at all there’s not many other things that can do it.

What role do you see an artist have in a current society?

It sounds like an oxymoron, but really, artists are, the clergy of a secular society, so for better or worse, the large bulk of the the society is not very religious and so they need a bit of information. Existential, ontological that you might have got from religion in the old days. But because that avenue is closed down to a lot of people, that’s the artist’s role. The artists can give you some meaning to potentially, if it’s good art, meaning to your existence. So it’s a big, important role.

I mean, the government obviously doesn’t think it’s very important because it doesn’t produce income, money, tax or whatever. But if it stops people being mentally ill and it keeps people happy, surely that’s more important than just some large number on some spreadsheet somewhere or other?

Would you be able to describe your art in three words?

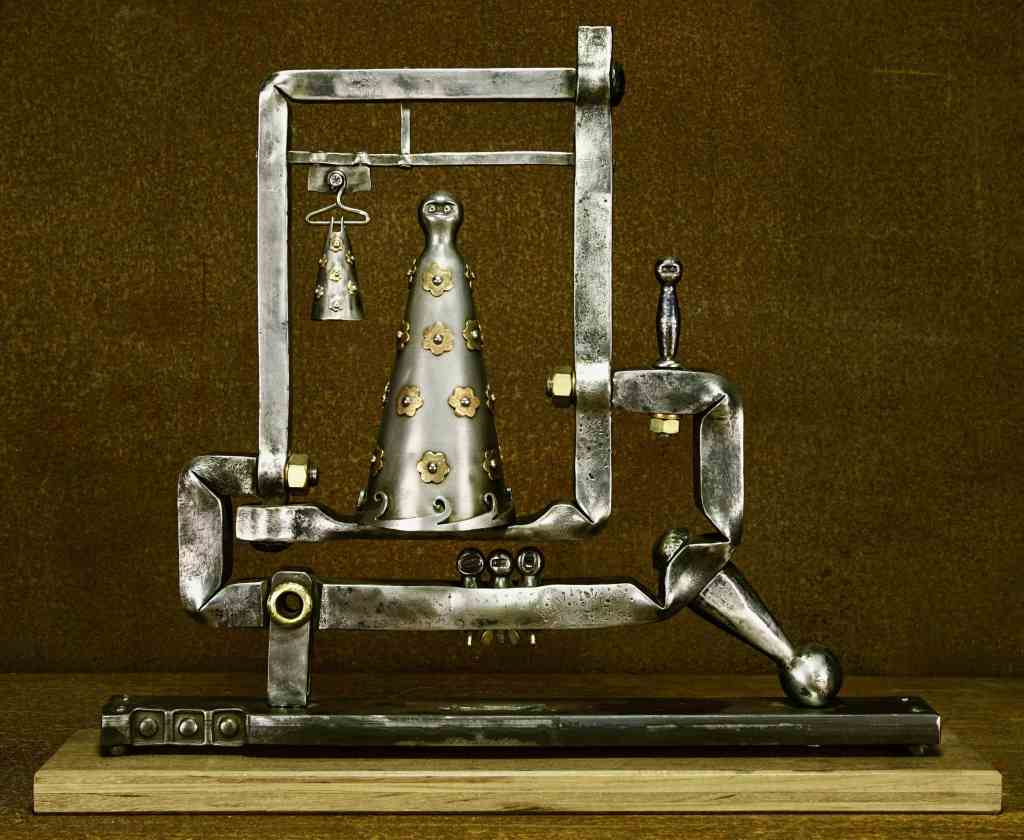

I thought about this. I was thinking some of the questions are a bit zoomed out. This is obviously a bit zoomed in. So I was thinking heavy, because they clearly are heavy I was thinking meaningful because they are meaningful to me. They’re not just something that looks nice. And I think, I mean, icon means different things to different people, but icon, they are icons for me. You did ask me where do I get my influences from? It is from religious, buddhist and hindu art and usually the earlier stuff, you know, like 9th century as it gets newer, it gets less good, in my opinion. So I would like to think I’m making modern icons.

Three words to describe yourself?

Well, it’s dad, husband, blacksmith and I’ve got to keep it in that order because if I focus too much on the blacksmithing, the blacksmithing gets less good. So you would have thought if I was single minded blacksmith, I’d be the best blacksmith. But it doesn’t work like that.

You have to be good at the other two things before you can be any good at a blacksmith. That’s my experience.

Softening The Blow Exhibition

See the exhibition in The Sadler Room at The Cooper Gallery until 29 March 2025. For more information, visit our website

If you enjoyed this blog you maybe interested in this article and video by John Holt